Frame by Paul Barnes

Recycling Caslon

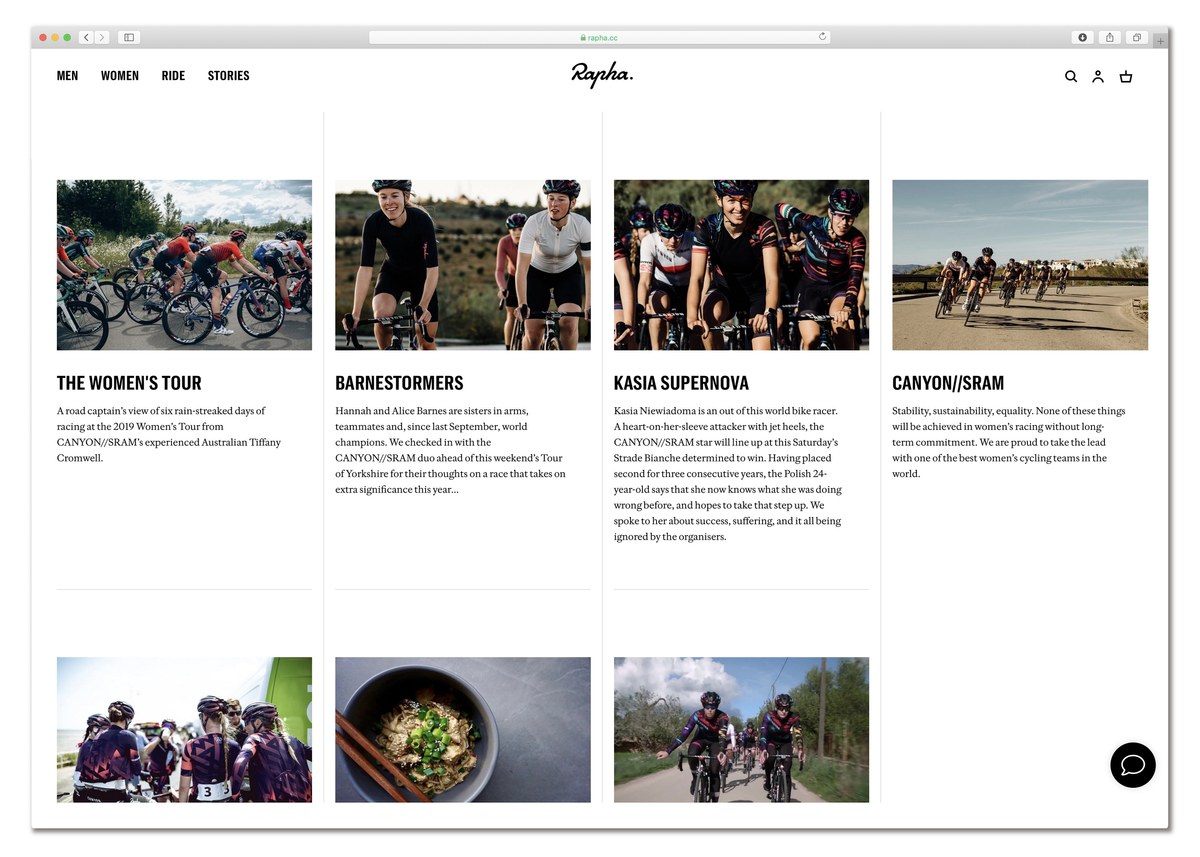

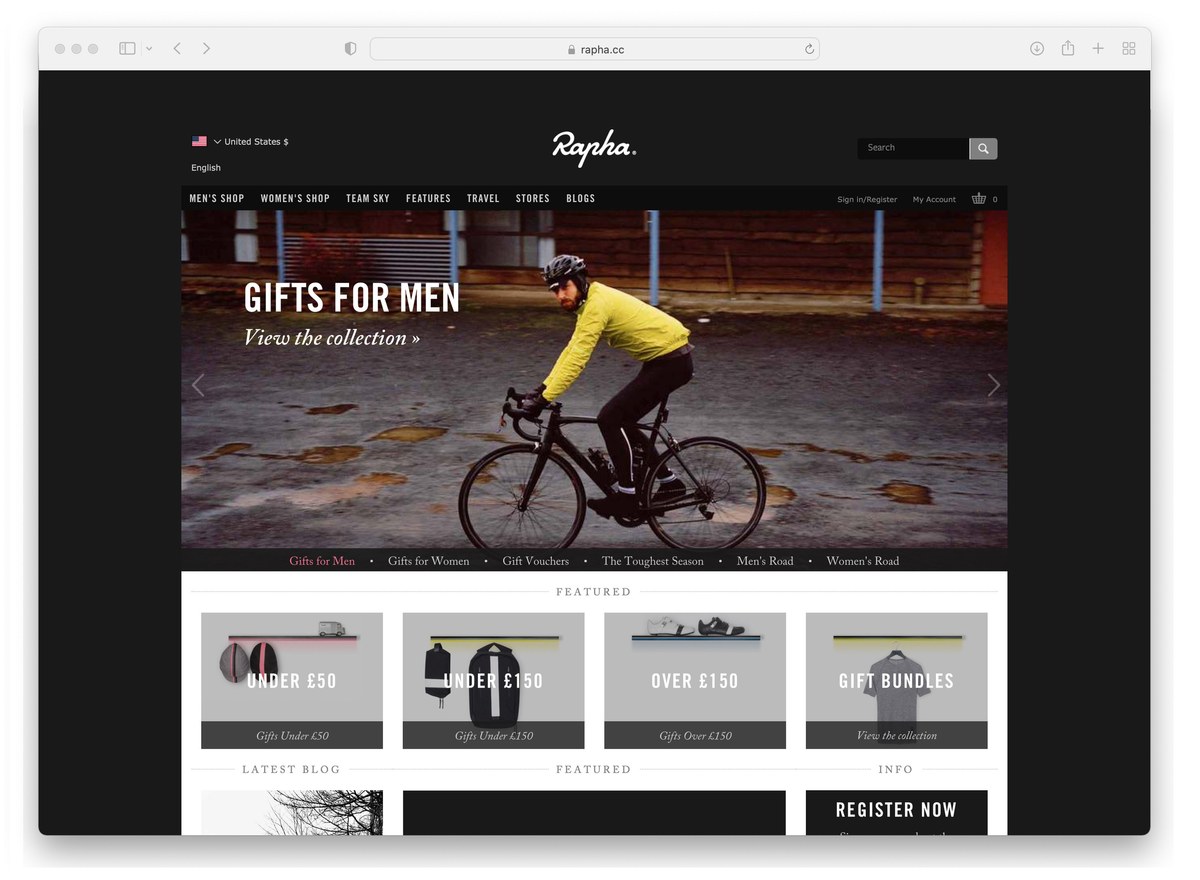

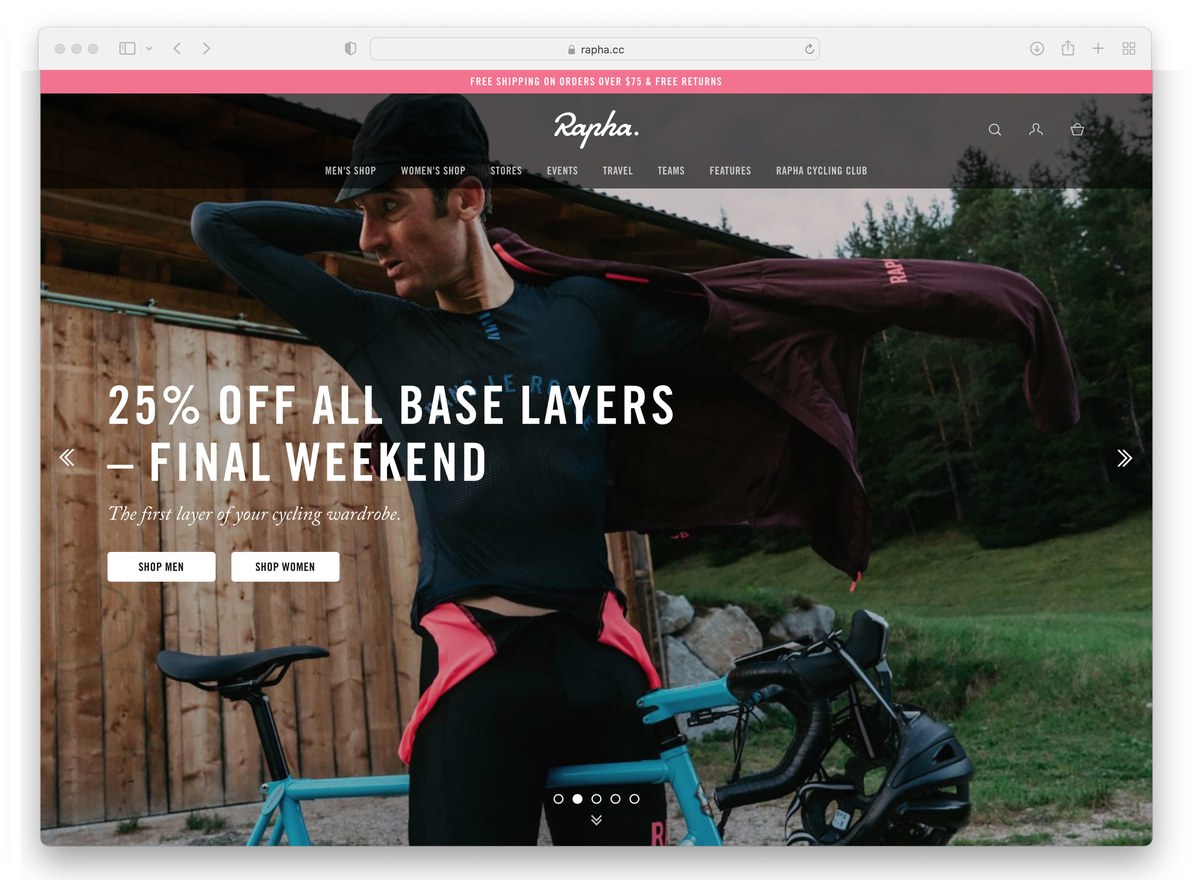

For many years, Rapha had a simple typographic approach: a condensed sans, Trade Gothic, matched with a serif, which in recent years was Adobe Caslon. The company planned to relaunch its website in 2019, with a development of the existing system rather than a wholesale change. Some elements worked, others less so. In the case of Adobe Caslon, though the face had a serious but warm aesthetic, it was uneconomical in headlines due to its relatively small x-height and generous extenders. The brand’s propensity to use italic was not based on an aesthetic choice or its effectiveness as a tool for emphasis, but rather on the italic’s narrowness compared to the roman.

Working with Rapha’s design director, Jack Saunders, Paul Barnes wondered if a new, more economical Caslon that still worked for both text and headlines was possible. What makes a Caslon a Caslon is a well-worn tread many contemporary type designers tackle, and one that Barnes previously avoided for that very reason. But here, new ground and new possibilities were revealed: were the relatively long ascenders and descenders in Adobe Caslon an intrinsic part of Caslon? More importantly, could a new design appear close enough to Caslon to most who would see it, but still differ significantly enough to make the process worthwhile?

Cycling and type are natural allies. Both disciplines are highly repetitive activities; whether pedalling across dozens of kilometres or spacing and kerning the same letters, there’s a sense of doing something over and over again. At the professional level, both require dedication and long hours to achieve good results, and often this excellence is regarded as an individual pursuit. Coincidentally, the traditional heartlands of cycling – the Low Countries (the Netherlands and Belgium), France, and Italy – were also centres of printing and typography. Both have a close relationship to their history and legend: just as a type aficionado might know that Claude Garamond created the definitive form of the Renaissance roman, a hardcore cycling fan will recall Eddy Merckx’s seventeenth-stage victory at the 1969 Tour de France. These historical moments are the cornerstones against which we measure other achievements.

As in type, professional cycling has also always had a close relationship with journalism, newspapers, and the wider media. The three major national stage races – the Tour de France (L’Auto, 1903), the Giro d’Italia (La Gazzetta dello Sport, 1909), and the Vuelta España (Informaciones, 1935) – were all initially set up by newspapers to boost circulation, and the press in turn promoted and documented these events. Many races, like the classics Ronde van Vlaanderen (Tour of Flanders) and Omloop Het Nieuwsblad (originally Omloop Het Volk), were also started by newspapers and others, such as Paris-Roubaix, relied on newspapers’ support. From the earliest days of the professional sport, letters and typography were everywhere: on the bikes, riders’ jerseys, the pinned race numbers, and the banners at the start and finish. And just as the clothes, hairstyles, and cars all date the scene, so does the typography.

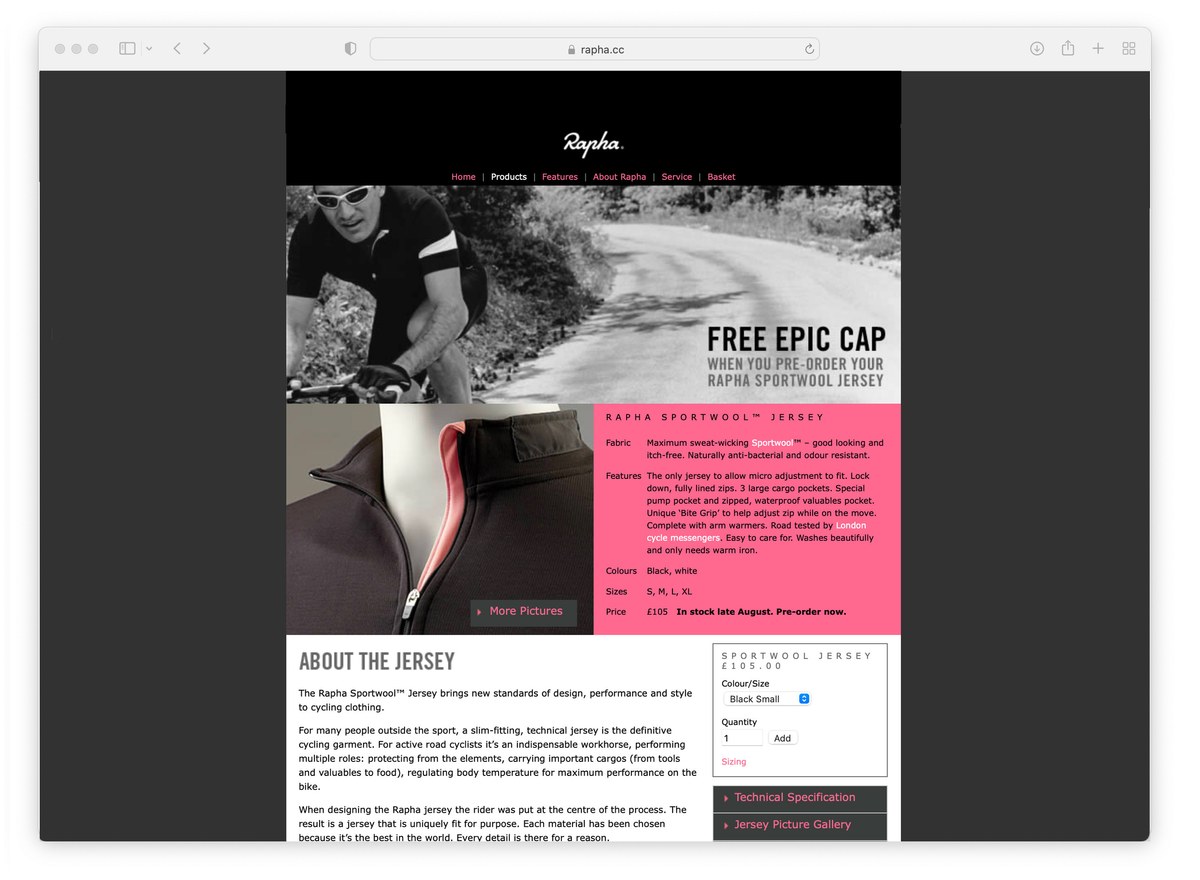

As a design-led company, Rapha has always been conscious of the relationship between cycling and typography. When it launched, the black-and-white photographs combined with a script logo and tracked-out all-sans capital style elicited a golden moment of cycling in the post-Second World War era, a rejection of the current visual landscape of cycling with its garish colours and questionable reputation. (Trade Gothic was matched with several serif fonts: Sabon, Clarendon, and eventually Adobe Caslon. The choice of Adobe Caslon perhaps had to do with its ready availability: Adobe started bundling it with its Creative Suite in 2003.) Even the name Rapha is evocative and specific, recalling the cycling team Saint Raphaël, sponsored by the French apertif from 1954 to 1964, and its directeur sportif Raphaël Géminiani. (‘The Original Rapha’, The Inner Ring, 16 May, 2012. As the article points out, at some point the main team had a sister team, Rapha–Gitane–Dunlop.)

Double Dutch

When Rapha first approached Commercial Type, Barnes had never thought of making any kind of Caslon, having long had an ambivalent relationship with the most British of faces. He felt that many revivals, such as Adobe Caslon and Big Caslon, reflected all that could be said of the first Caslon. Although much of Commercial Classics draws upon the work of later generations of the Caslon foundry, Barnes had little curiosity about looking at William Caslon I’s work – including the master’s first roman from 1725. It was only when Saunders chose Caslon Doric and wanted a serif with similar proportions that Barnes started to examine Caslon afresh, leading him down the path to make Frame.

Frame’s origins are rooted in the founder’s seriffed faces, which in turn were derived from the Dutch typefounders of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Discerning printers pre-Caslon would have imported type from the Low Countries. These so-called Dutch-style types were characterized by narrower faces with increased x-height and shorter extenders, innovations that, because they allowed more words to a page, were economical both in their use of space and financially. Throughout the ensuing centuries, the tall x-height and abbreviated ascenders and descenders were exaggerated even more, and the phrase ‘Dutch style’ now alludes to the more modern newspaper faces of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Updating the Caslon tradition and returning to Caslon’s Dutch heritage, Frame in this sense is a copy of a copy.

Designing Frame

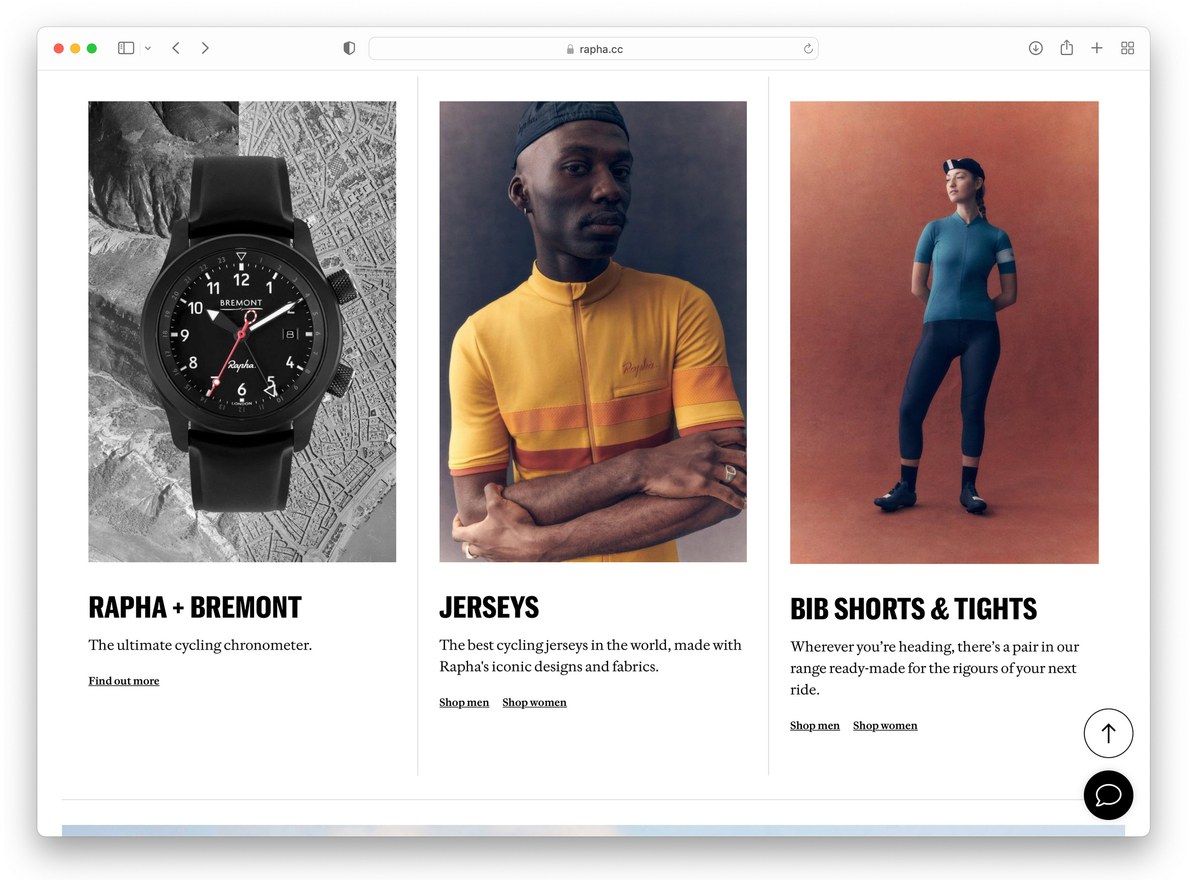

Several design decisions allowed Barnes to find the freedom to make Frame, a Caslon for the twenty-first century. The first was where the typeface would appear, primarily as a digital face living online. Secondly, the softness inherent in Adobe Caslon suggests the effect of letterpress squash and would now be unnecessary: Frame could have a new, crisp character. The critical moment came when Caslon Doric was chosen to replace Trade Gothic and the decision was made that the new serif face should match the vertical cap- and x-height proportions of the sans. Enlarging the lowercase would give the new serif a more modern Dutch appearance. This reminded Barnes of Publico, a serif face designed with Christian Schwartz to match the proportions of the original Helvetica.

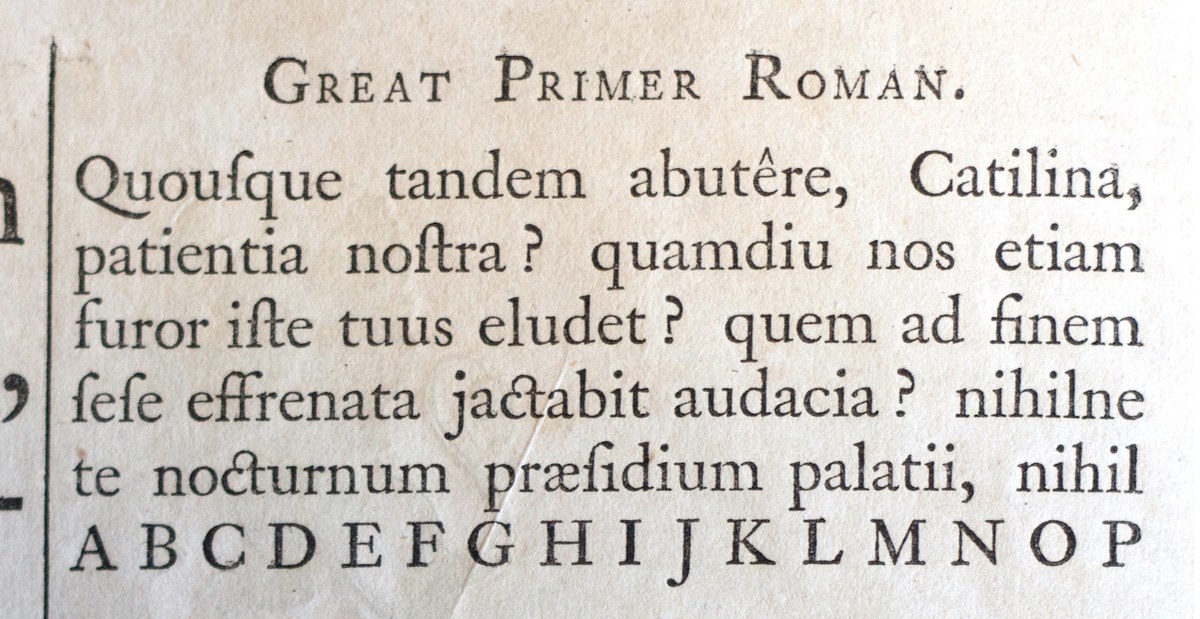

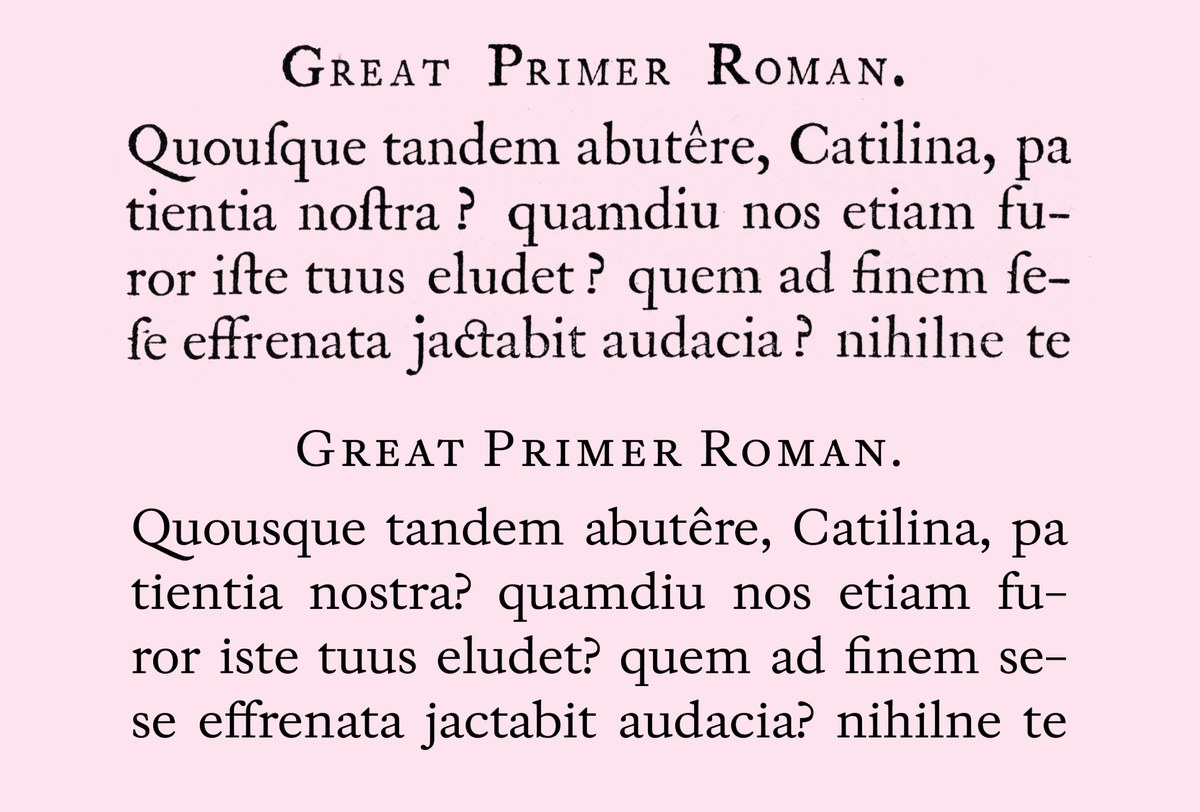

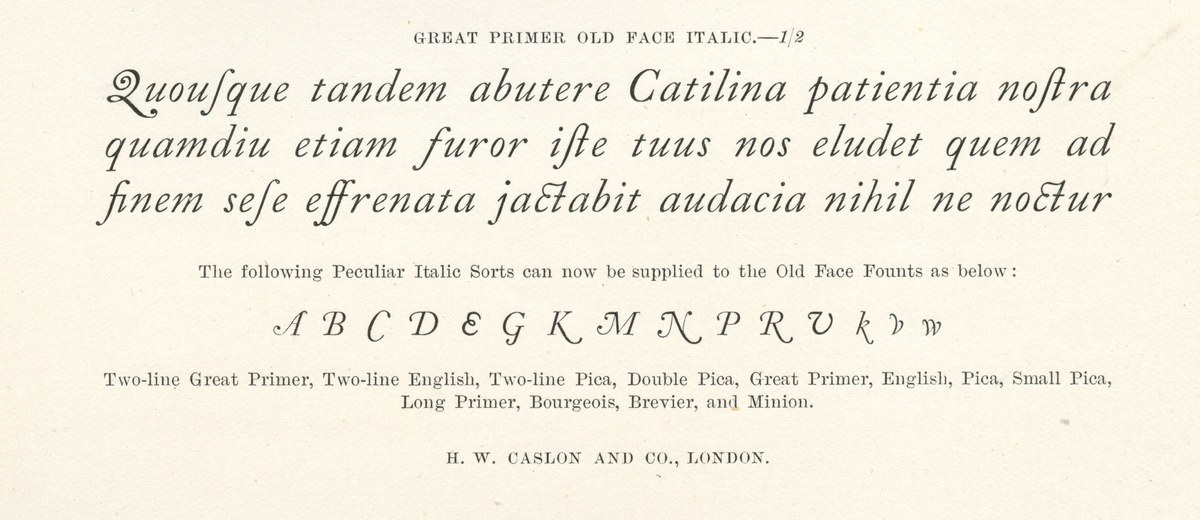

As one of the earliest William Caslon I faces cut in 1734, Great Primer is probably the Caslon text face that comes closest to the Dutch style. Great Primer was particularly appealing as a source because it retains the sharpness and grittiness of the masters of the Low Countries in the seventeenth century. Grittiness was important to Barnes, as it’s a quality that is highly regarded in professional cycling – the tradition of the strong, able to ride at the front into the headwind, whatever the conditions. These attributes are especially valued in the Low Countries and in the classic races like Paris-Roubaix and the Ronde van Vlaanderen.

Frame diverges most noticeably from Caslon’s Great Primer and Adobe Caslon in its proportions and in the reduction of details to simpler forms. At text sizes, many details become lost and streamlining the forms also returns a sharpness to the overall personality of the face. In several of Caslon’s faces, the serif structure in the lowercase is almost a flat line, with little or no tapering. Frame’s lowercase serifs have gentle straight flaring of the stroke, and the serif itself is a shallow, nearly flat stroke, ending in an angled terminal. In the capitals, the stroke flares before meeting an angled corner and then tapers. The balls are rounded on the outside but flat on the inside, shifting between roundness and angularity. The contrast is deliberately low in the Text face, almost matching Adobe Caslon. Certain letterforms are drawn from the Dutch style rather than Caslon: for example, the lack of top and bottom serifs on the C, G, and S. By rescaling the proportions, the capitals that are quite prominent in the Caslons leave less of an impact on the overall colour of a page set in Frame.

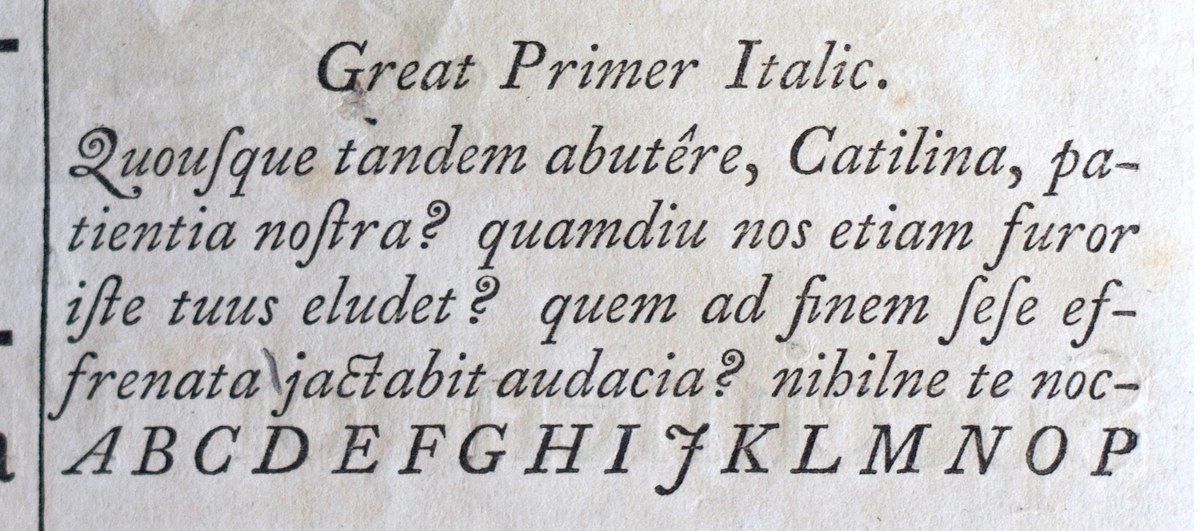

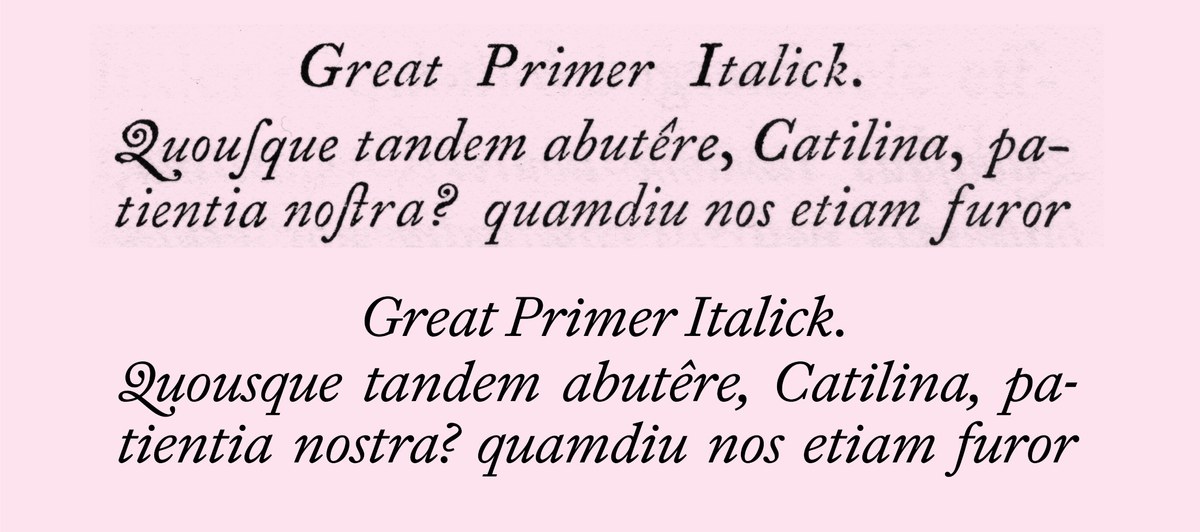

Caslon’s italics show a variety of styles. The largest sizes narrow in width, with a shallow angle and tight spacing. The Text sizes’ angles frequently vary, from steep in Great Primer to something gentler in Pica; the width also varies, from Great Primer at its widest, to Pica at its narrowest (like Adobe Caslon). In contrast to earlier models, such as the French master Granjon of the sixteenth century, Caslon’s italics have fewer changes in angle and width to maintain a steadier rhythm. Where Granjon’s italics often overshadow the roman, Caslon’s assume a much more subservient role and are far less dramatic. Frame has the regularity of Caslon’s faces, with its angle and width falling in the middle of the original smaller sizes and Great Primer.

As with the roman, the details of the italic are reductionist. The capitals follow exactly the same serif structure, while the tails reach the main strokes in a sharp and obvious point in the lowercase and their exteriors have a subtle, barely noticeable juncture. Simplifying some characters maintains rhythm, smoothes out the overall colour, and improves legibility. The h lacks an inward ball terminal to maintain the rhythm of the n and m, and the v and w are gently curved, rather than having rounded bowls with head, stroke, and ball.

The swash letters that appear in Caslon specimens from the latter part of the nineteenth century, as well as in many modern Caslon revivals, were not cut for the original in 1730 (bar the J and Q), but added later. They have a different flavour from the corresponding eighteenth-century letters and lack the confidence and majesty of those made in the sixteenth century. In Frame, the swashes are informed by the drama of Granjon, but tempered by the calmer qualities of the lowercase.

Overall, the italic attempts to capture the spirit and energy of Caslon’s original, but with the measuredness and regularity needed for legibility. Although the roman addressed many of Rapha’s concerns about economy, the italic remains a popular choice for headlines, where its understated elegance draws readers’ attention without overpowering.

Head and Body Copy

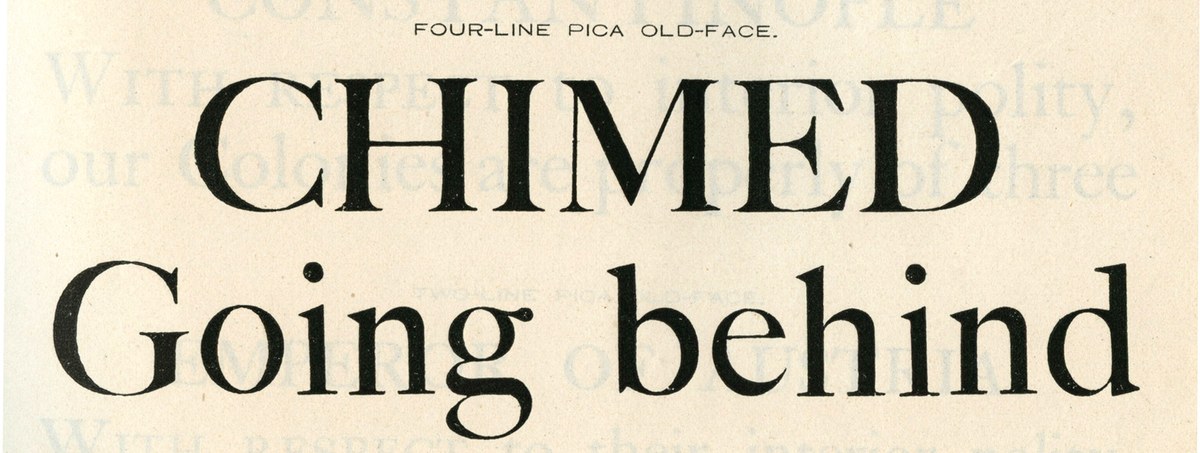

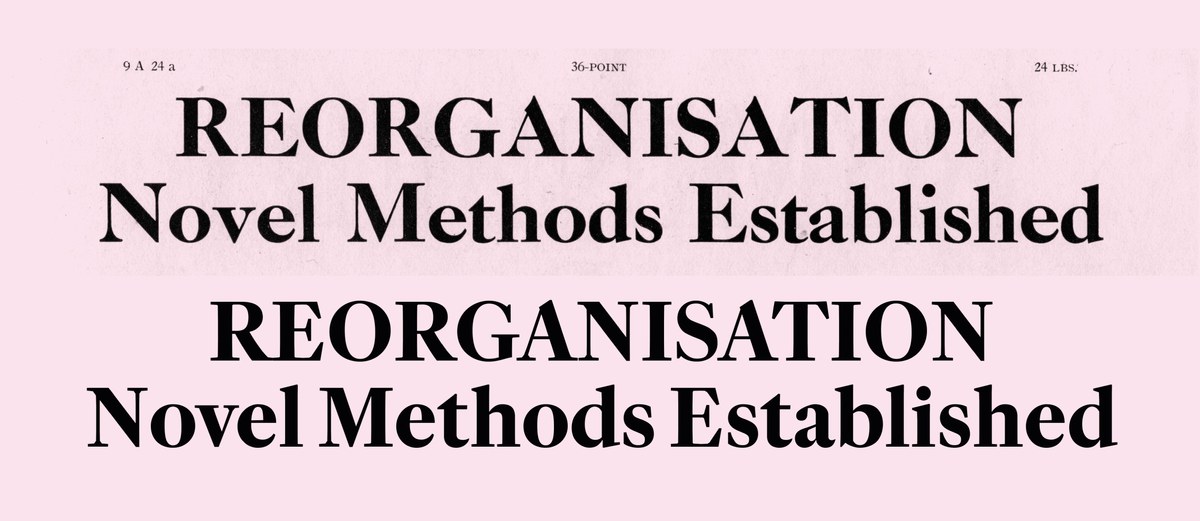

In the age of Caslon, every size of type was cut individually, although the average reader hardly would have noticed how the design changed between sizes. Adobe Caslon and Big Caslon are based on William Caslon’s vision, but a side-by-side comparison shows that they are quite different. They diverge not only in their degree of contrast but also in width, proportion, and spacing. Yet, both are accepted as one and the same: Caslon. Only when type stopped being cut by hand did it gain the greater consistency users expect today. In the case of Frame, the headline variants are closer to the modern approach of adapting the text rather than remaking it, in this case by increasing contrast and tightening spacing for use at sizes above 18pt. Though the headline is sharper and crisper, it is not as extreme as a hairline Modern.

Bolder and Bolder

Without a model, a convincing bold had to be created that retained the ethos of the regular weight while dealing with the challenges of becoming heavier. As weight increases, the x-height rises to avoid the letters becoming too wide. Thus the small number of weights (four in total) reflects both the client’s need for only a bold, and not heavier weight; and remains true to the original design without becoming a caricature. When Rapha requires darker weight and greater emphasis, they can turn to Caslon Doric.

Frame is a typeface steeped in the rich tradition of Caslon and, by extension, the Dutch style. Yet while Frame echoes its predecessors, accounting for Rapha’s needs alchemized a truly contemporary style. Like many faces that follow Caslon, it is informed by the exigencies of time and place. In this case, sharing the proportions of Caslon Doric gives a unified identity and efficiency appropriate to the brand. Frame’s utility is proven across all mediums: from print and web to environmental and fashion design.