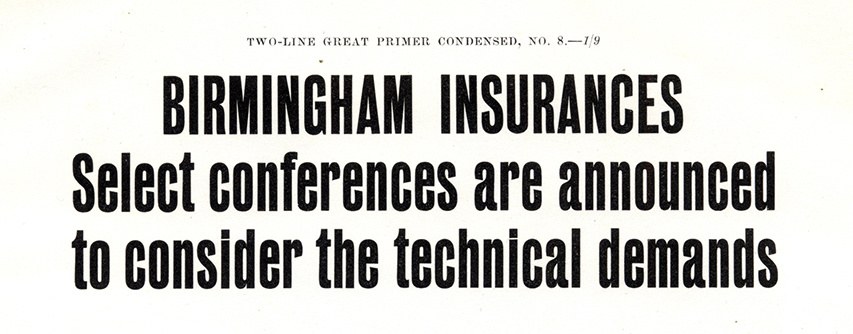

Caslon Doric

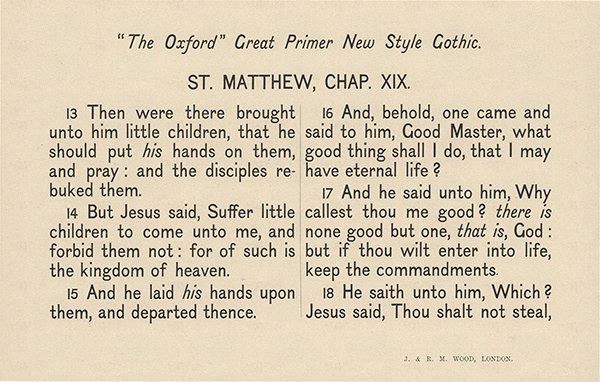

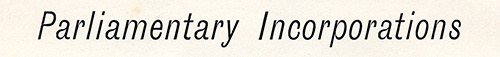

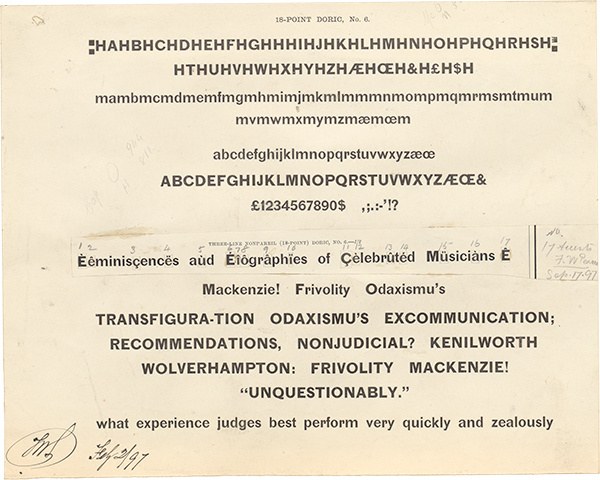

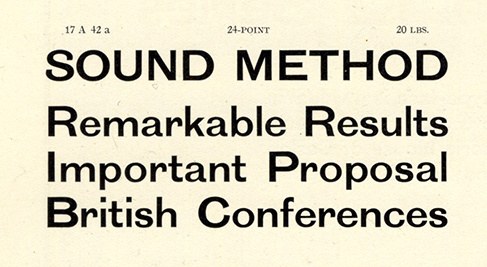

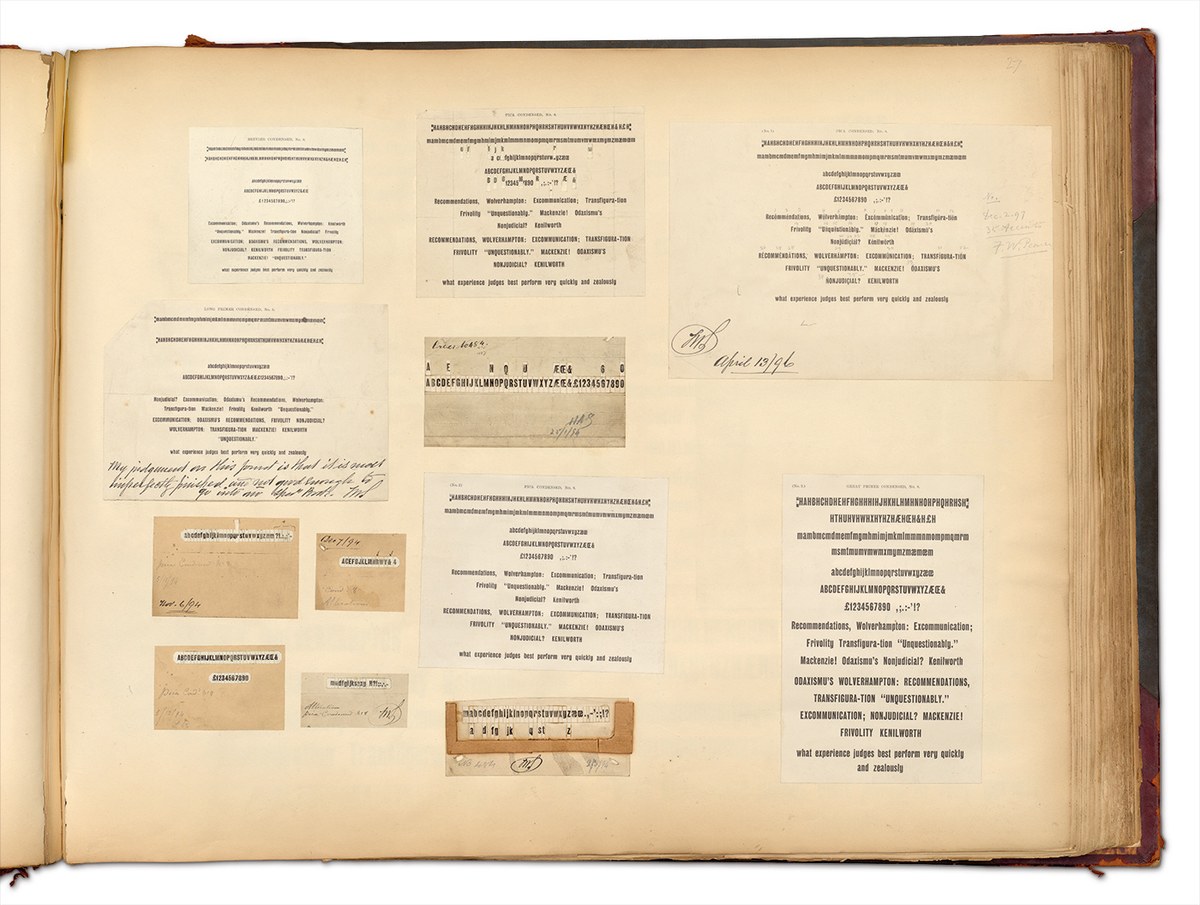

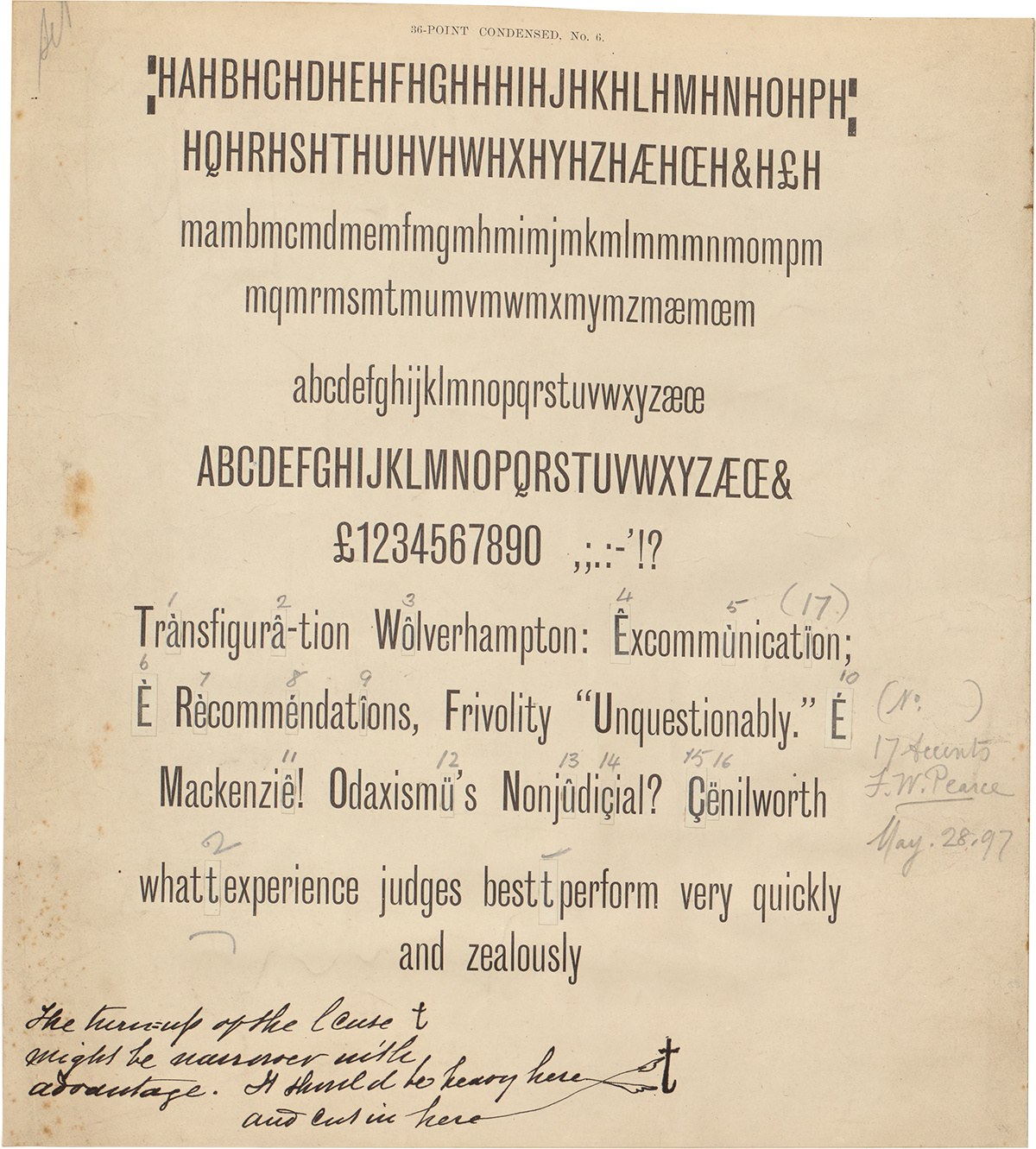

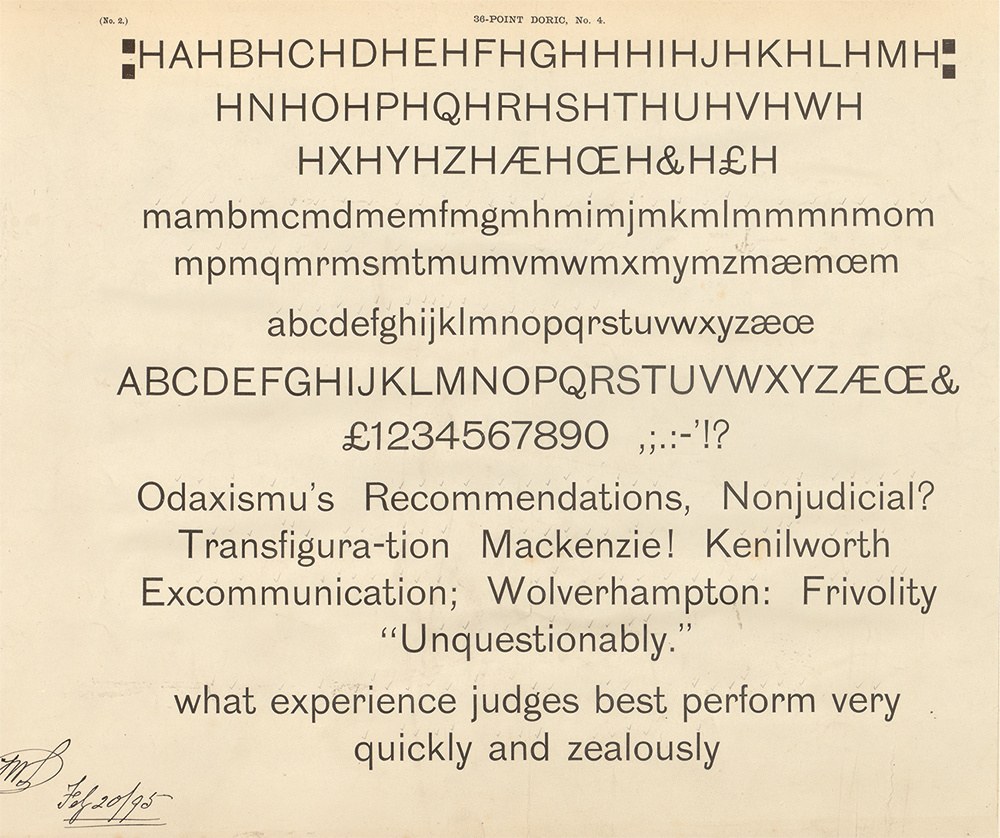

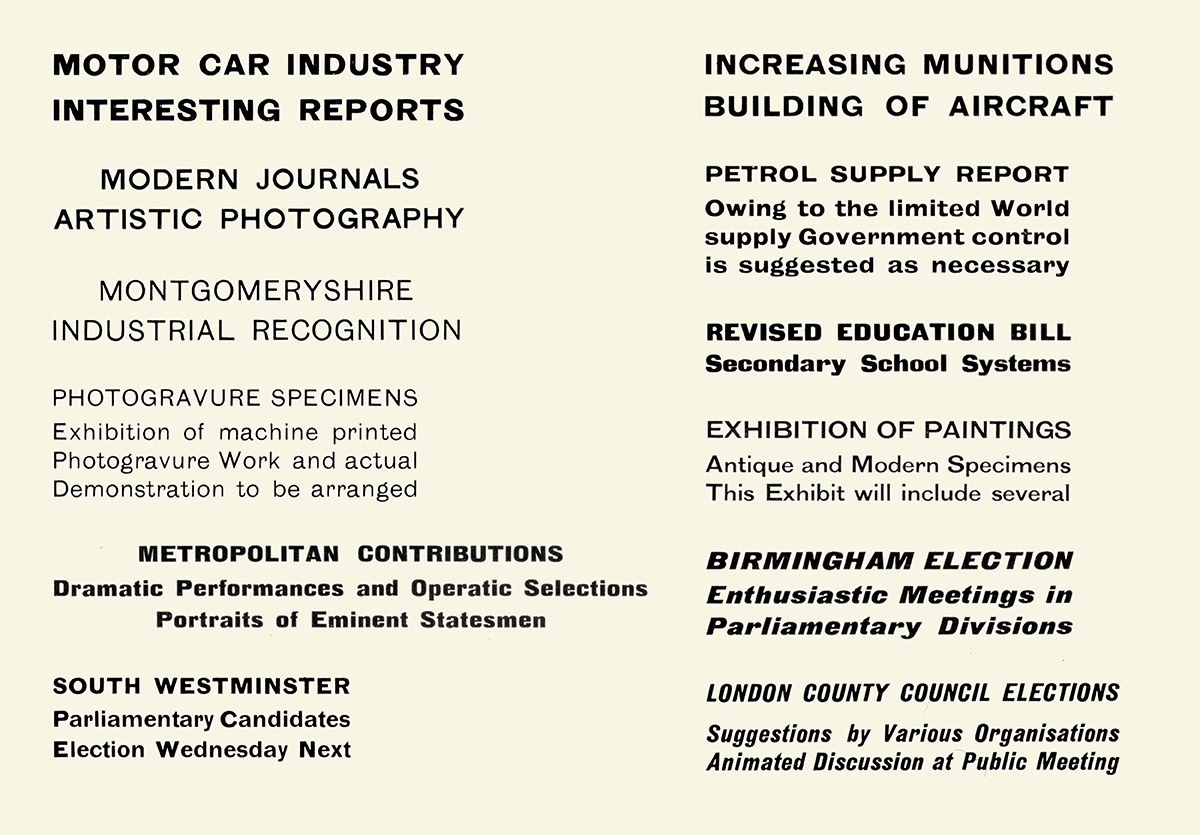

In the final quarter of the nineteenth century, the Caslon foundry invested heavily in the expansion of both its regular and narrow sans serifs. Starting in 1876, Caslon Doric No. 4 was cut as a regular weight, sans serif style in both upper- and lowercase. Here is a proof from the foundry in 1895 that shows the 36 point style (the foundry had started to use a point unit system for sizes by this date). St Bride Library.

Doric No. 4. Specimens of Printing Types, H. W. Caslon, 1895.

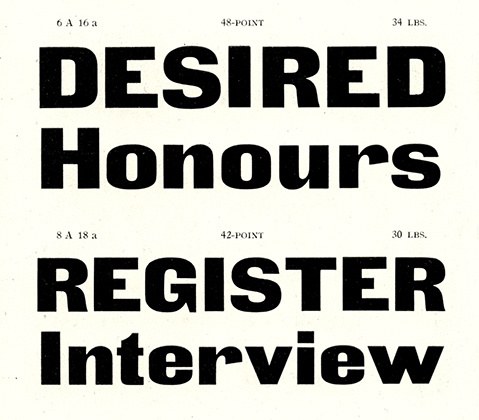

Bolder

Wider and Thinner

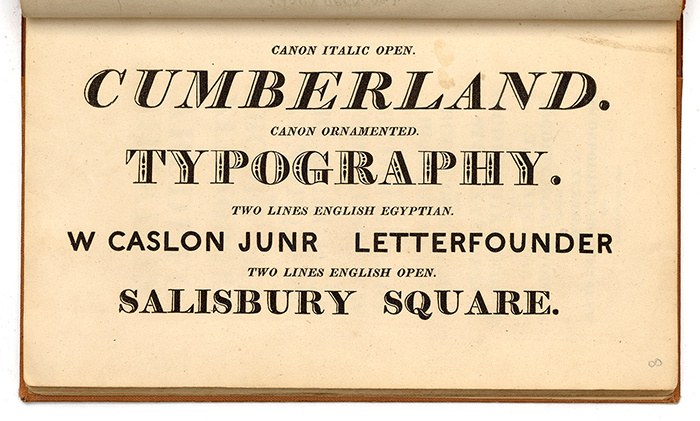

One of the earliest light sans typefaces, Pearl Skeleton. A Specimen of Printing Types by W. Thorowgood and Company, 1837.

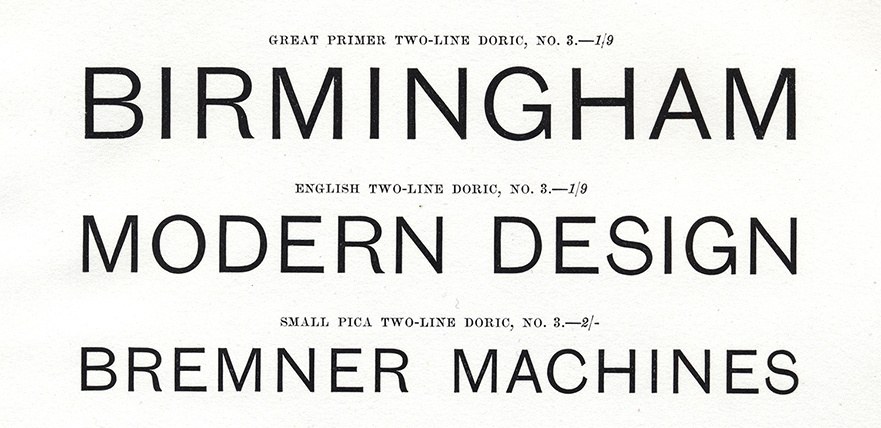

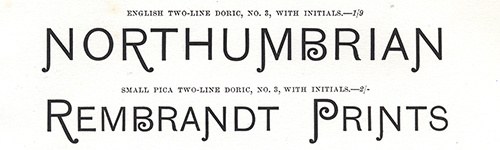

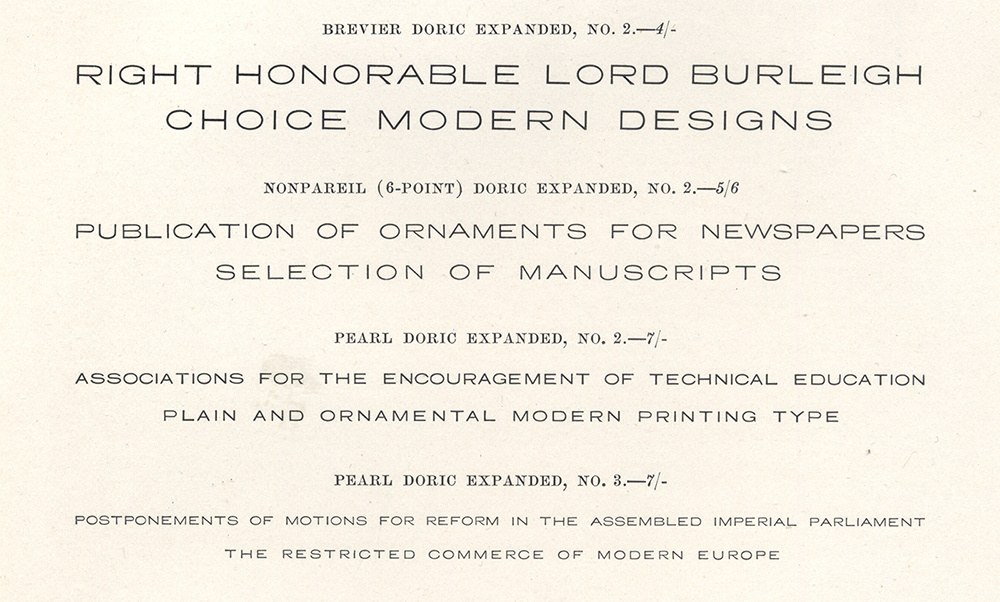

Doric Expanded from the 1850s. Specimens of Printing Types, H. W. Caslon, 1895.

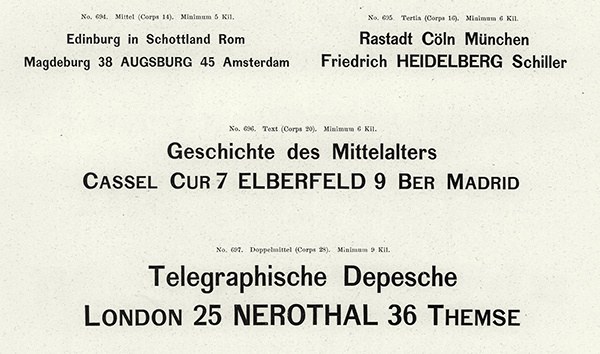

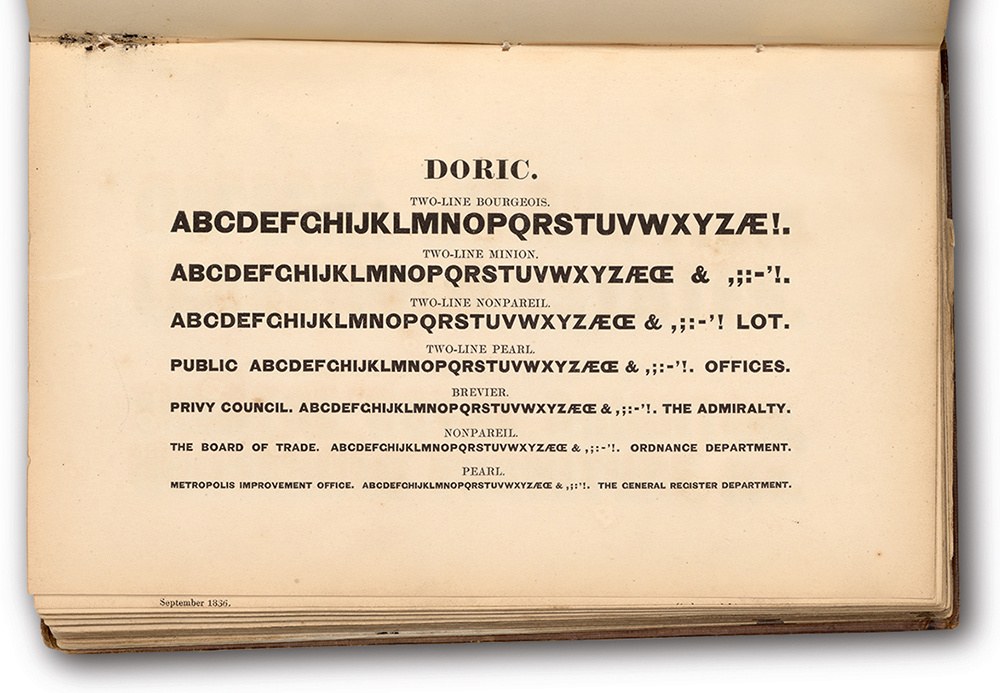

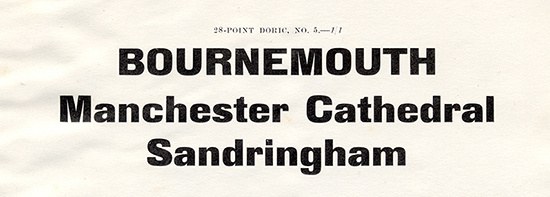

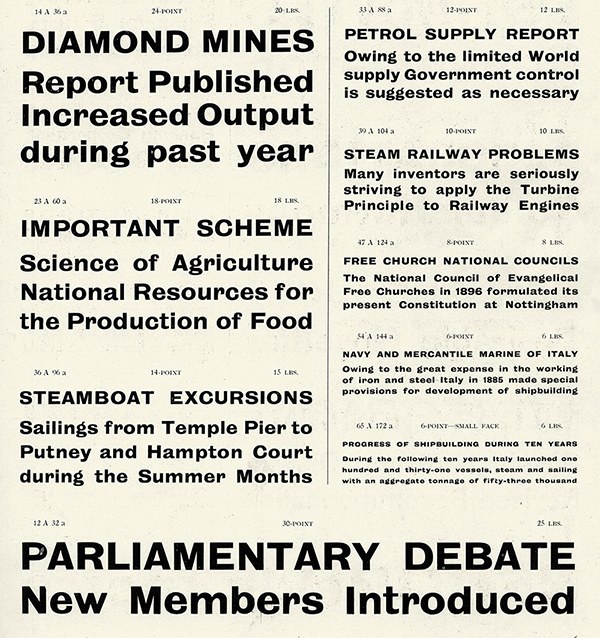

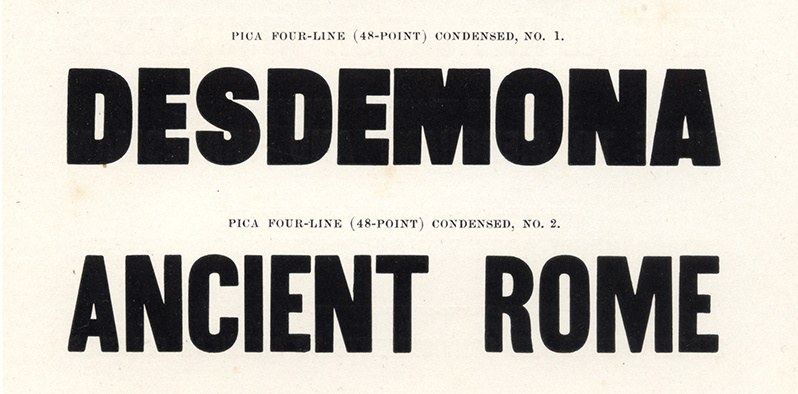

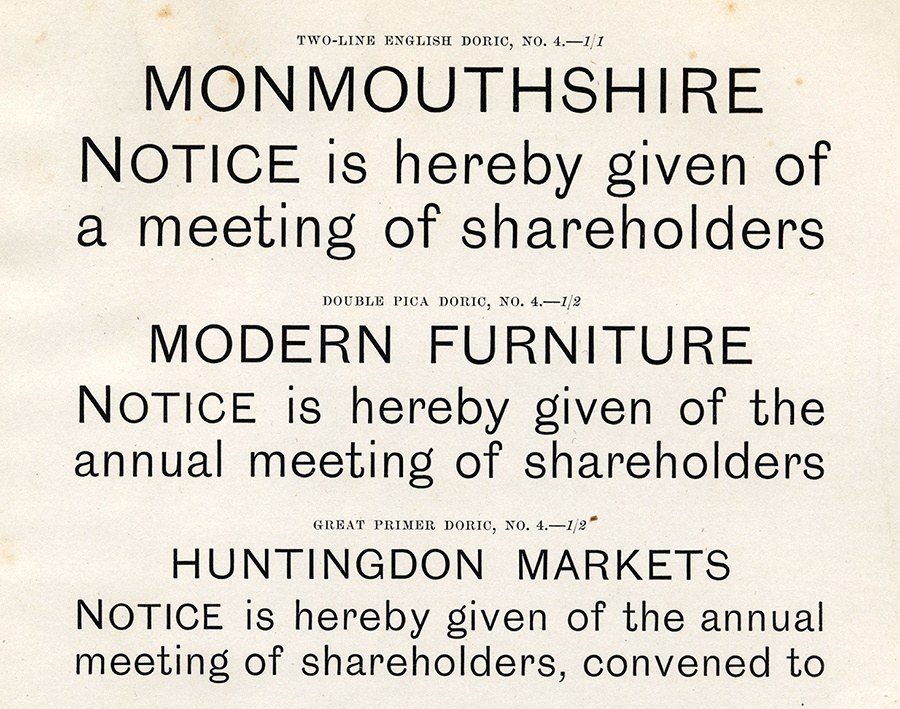

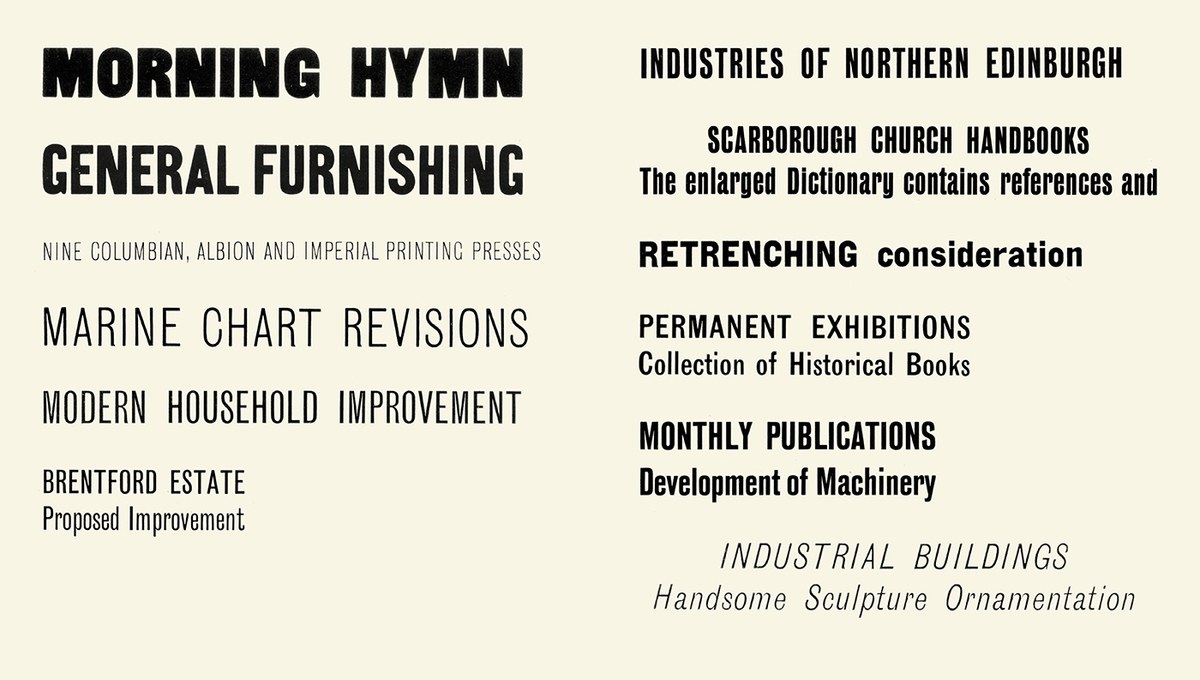

Caslon’s original Doric is a wider form than the sans of Figgins or Blake & Stephenson, but we would not necessarily recognise it as a wide design. Wide or expanded typefaces (the fat face appears to be the first to be stretched) seems a logical development after condensing forms, but as they take up more space than save and reduce the size a headline can be, they never gained the same popularity. Appearing first in the fourth decade, they gained some popularity in the 1840s and 1850s.

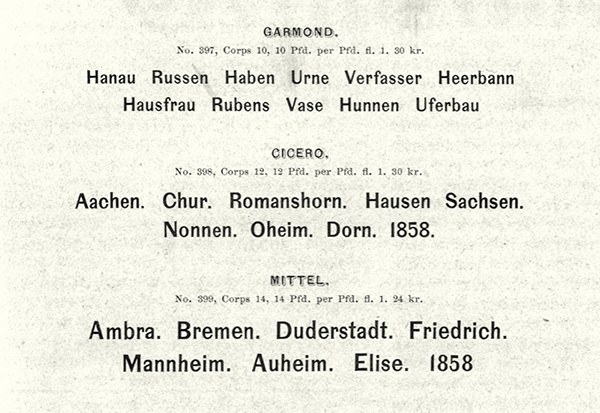

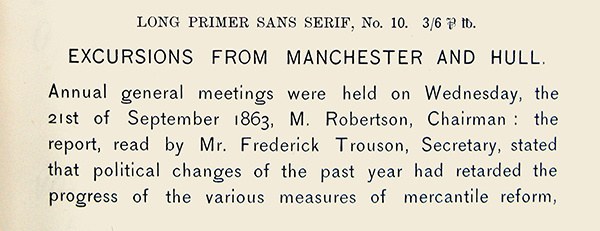

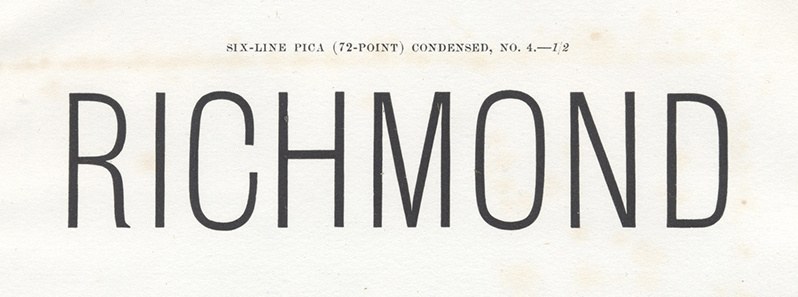

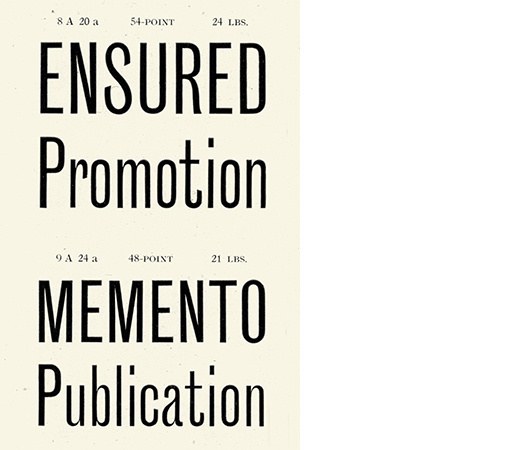

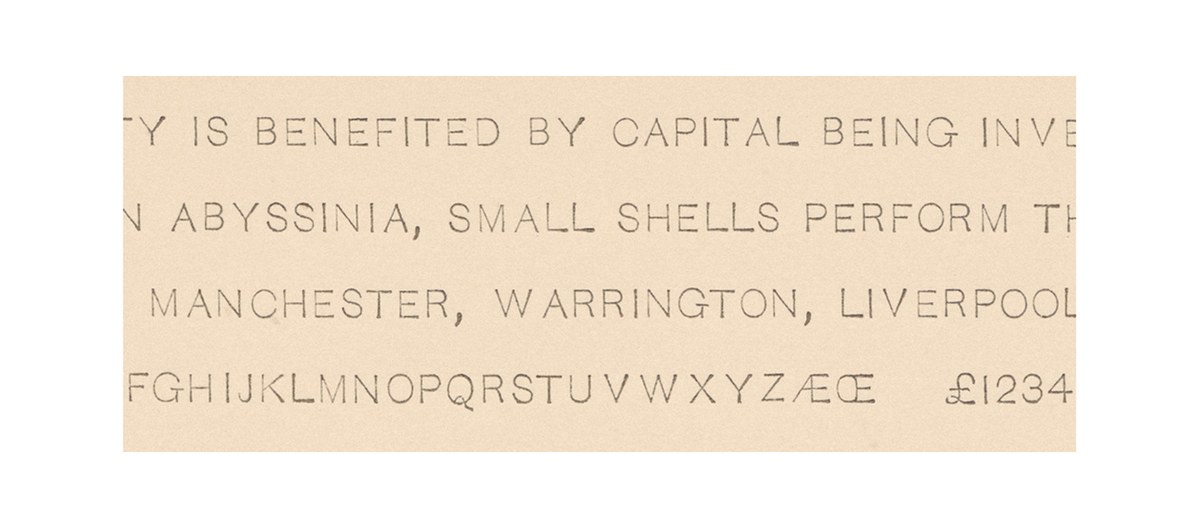

Certainly Doric No. 8 and No. 12 are wide, but these are not the first wide sans faces that the foundry produced. Doric Expanded appeared in the 1860s, which was used as a titling font. This light, all-capital style probably followed a letterform cut by engravers for visiting cards and announcements; its thinness is typical of the engraver rather than the typefounder. Thorowgood, for example, shows a regular width hairline style of sans in 1838, cut as we would expect at a small size. Founders at this time did not see this form as the model for a large range of sizes. The modern Doric imagines the forms of Doric No. 4 as being extrapolated into such light weights, but also in being stretched into wider than expected forms.

Narrower

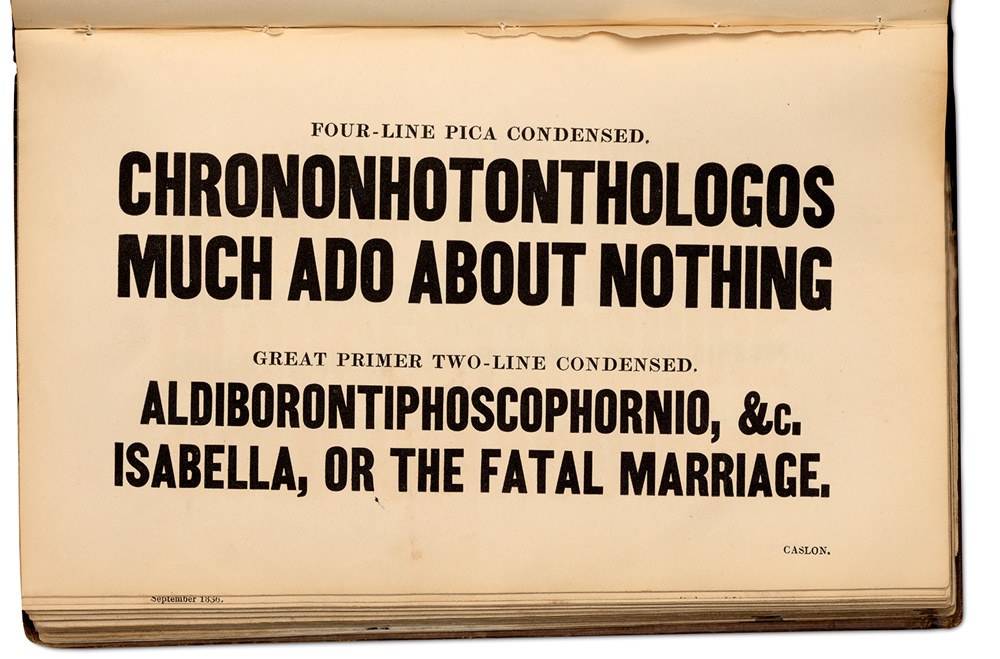

Caslon introduced the condensed sans in the 1830s following the example of the other foundries. Its usefulness is demonstrated with the setting of long titles of plays. But the typefaces remain simply titled ‘Condensed’, with Caslon only introducing the name Sans in the twentieth century. Chrononhotonthologos was the title of an eighteenth-century play, Aldiborontiphoscofornio being a character. Specimen of Printing Types by Henry Caslon, 1842.

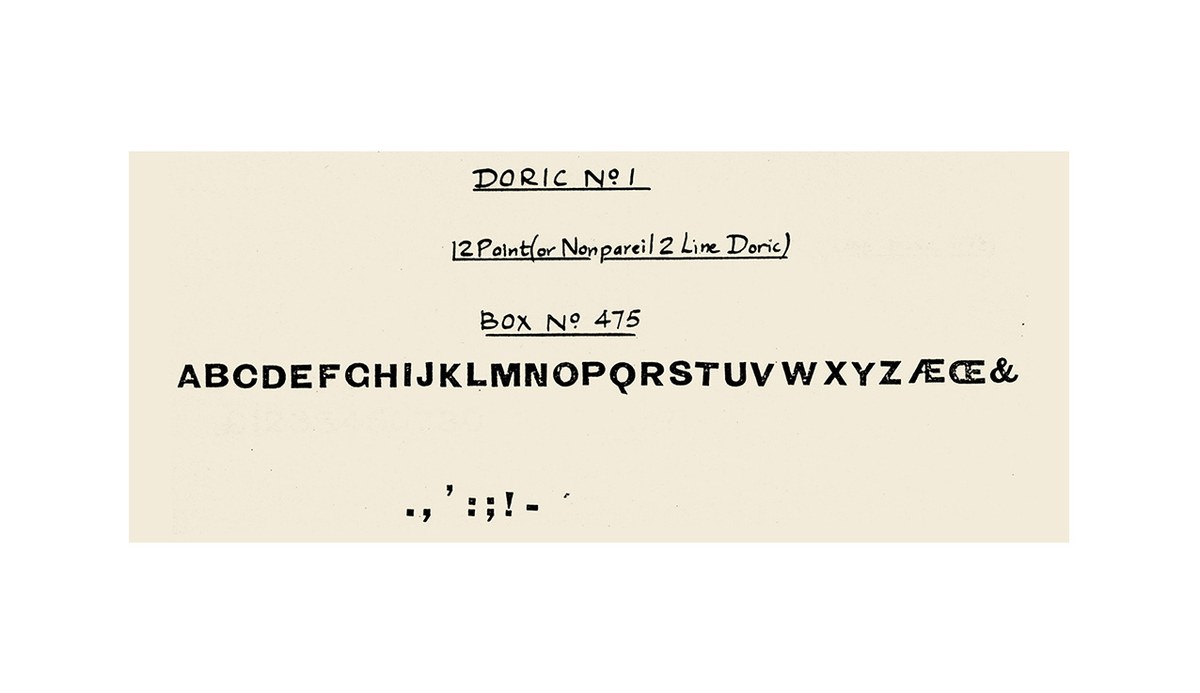

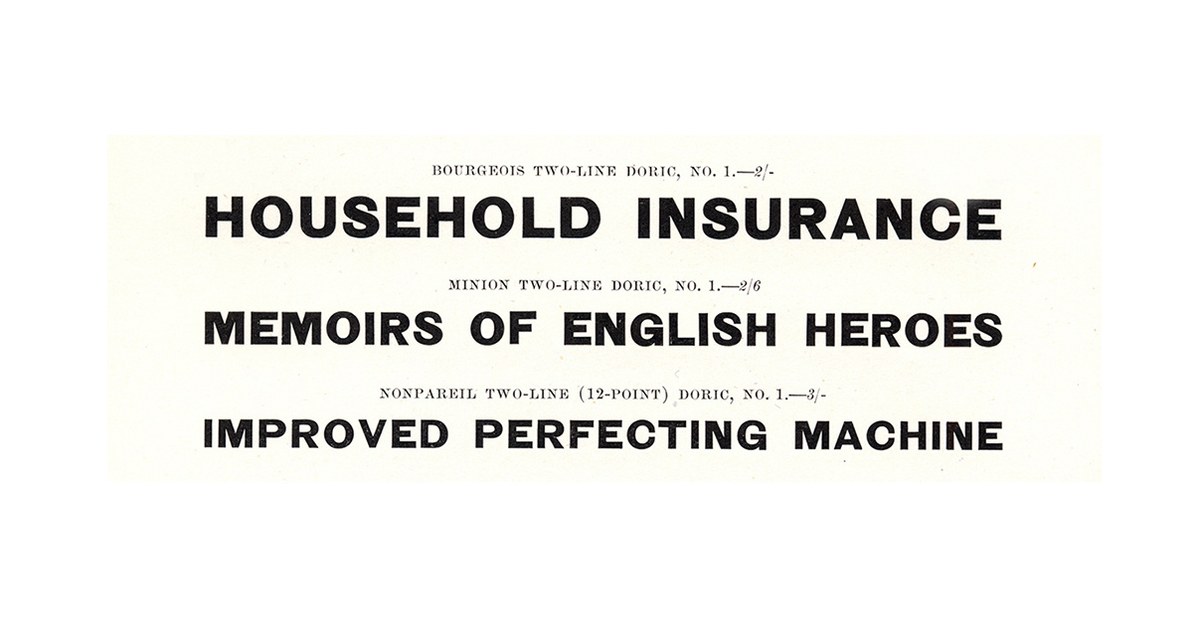

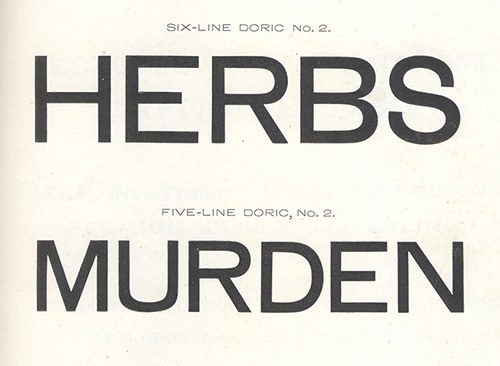

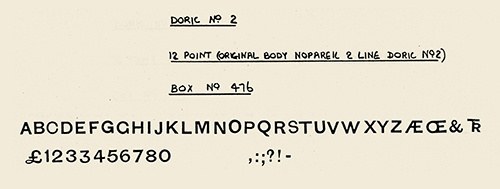

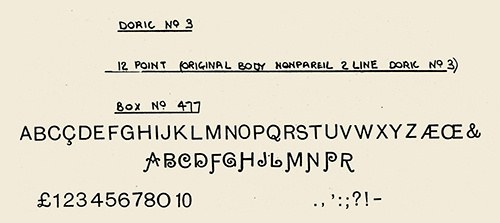

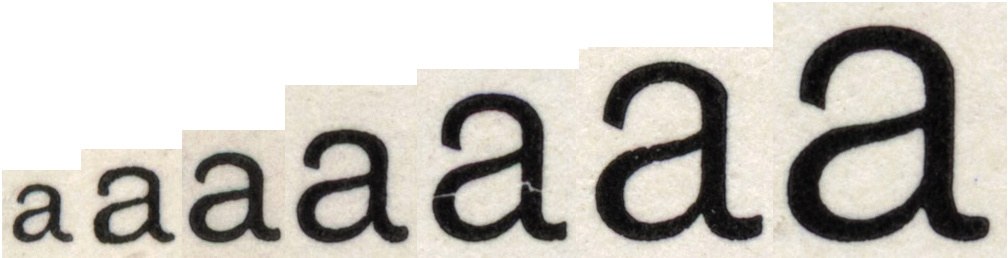

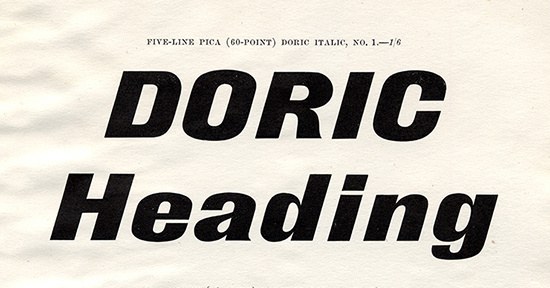

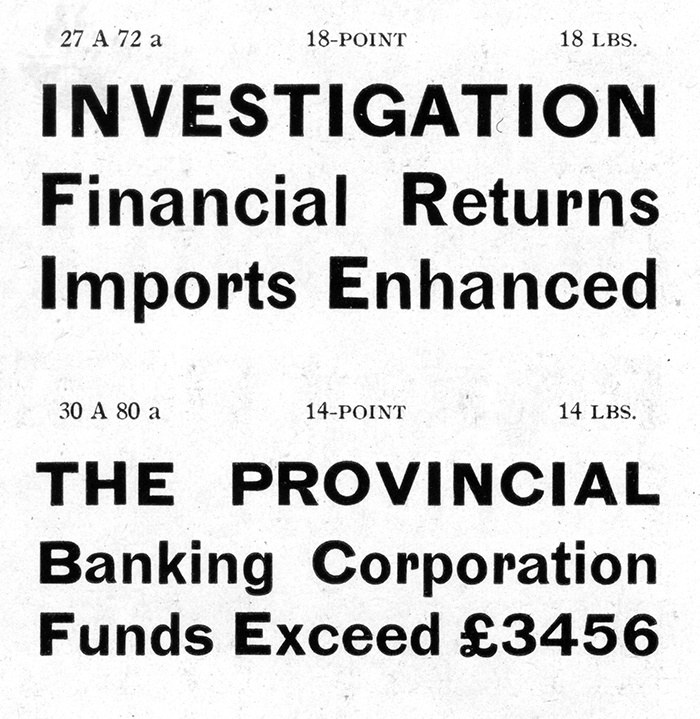

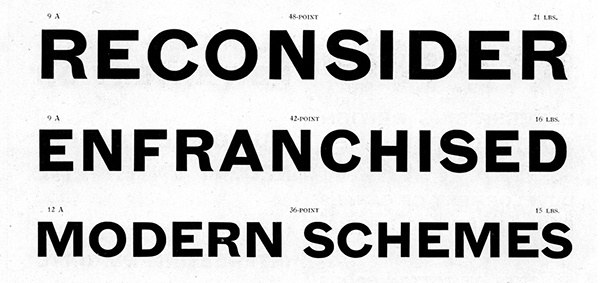

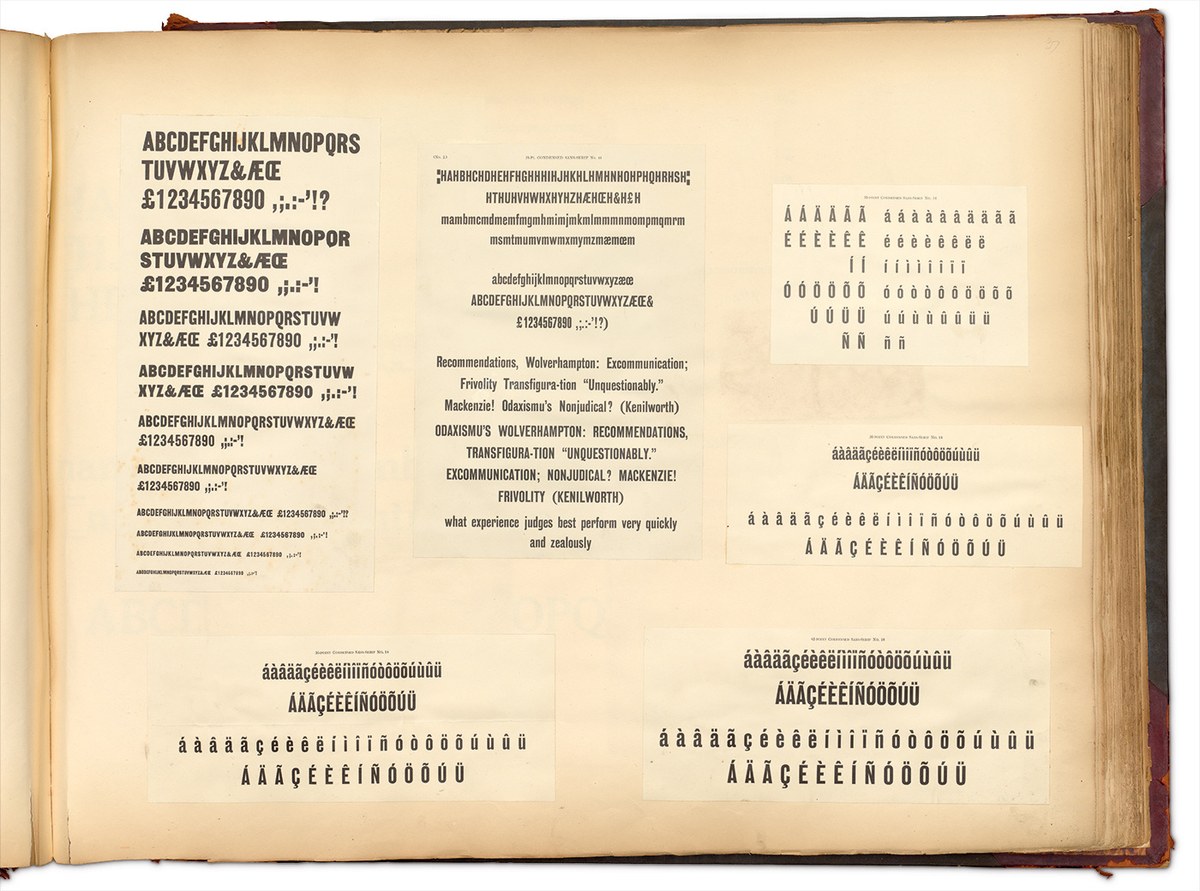

Caslon Doric through the ages. Left: Doric No. 1 (first appearance c. 1840), No. 2 (cut at Bower and Bacon before 1851), No. 3 (c. 1876), No. 4 (c. 1876; No. 3 and No. 4 are the same design, with the addition of lowercase in No. 4), No. 5 (c. 1895), and No. 6. (1896, based in part on Gothic No. 2 of the Central Type Foundry, St. Louis). Right: Doric No. 7 (1896 No. 6 and No. 7 are the same design, No. 7 being the titling capitals version), No. 8 (1906), No. 10 (1909), and No. 12 (1921). The italics are Doric Italic No. 1 (c. 1893, a copy of J. John Söhne’s Fette Kursiv-Grotesk) and No. 2 (after 1895 before 1900).

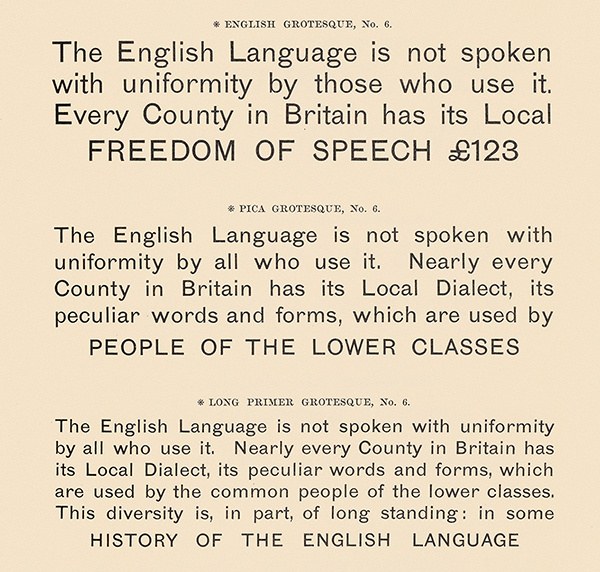

Caslon Sans though the ages. Left: Sans Serif No.1 (after 1833, before 1836), Sans Serif No. 2 (before 1842), Sans Serif No. 3 (before 1861), Sans Serif No. 4 (before 1861), Sans Serif No. 5 (before 1886), Sans Serif No. 6 (1895), Sans Serif No. 7 (1893). Right: Sans Serif No. 8 (1894), Sans Serif No. 10 (1894), Sans Serif No. 12 (which was renumbered from No. 9, 1899), and Sans Serif No. 14 (1912), Fourteen-Line Pica Condensed (1830s), Condensed Italic (before 1870).

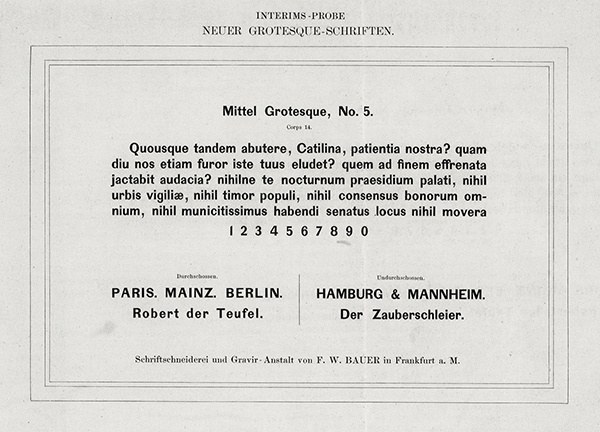

Caslon maintained its curious practice of labelling typefaces of the same style as variously Doric or sans serif into the twentieth century. It also did not adopt any of the newer humanist styles unlike other foundries, such as Stephenson Blake (Granby, 1930) and Monotype (Gill Sans, 1928), though they did market and import the geometric Elegant from the Stempel foundry. Whilst similar sans serifs, such as the German Schelter & Giesecke Grotesk or Bauer’s Venus, gained popularity amongst the continental modernists in the interwar years, no such movement existed in Britain that would champion Caslon’s Doric (or those designs of Miller & Richard or Stephenson Blake). And so, Caslon Doric dropped out of existence as the foundry collapsed in the 1930s, more than 120 years after Caslon IV first showed a sans type. In the years after the Second World War, the new wave of designers in Britain would also reject the British sans, whether it be Gill or the nineteenth-century forms, preferring the continental models, first of Monotype’s Grotesque 215 (a design similar to Venus) and latterly, the neo-grotesques of Helvetica and Univers.

With the revived Caslon Doric, we attempted to bring several disparate styles together and to make a system that makes sense to contemporary designers, while also trying to retain some of the diversity and warmth of the originals. Like many of the range of faces in Commercial Classics, much is imagined, yet feels authentic to what existed already.