Brunel

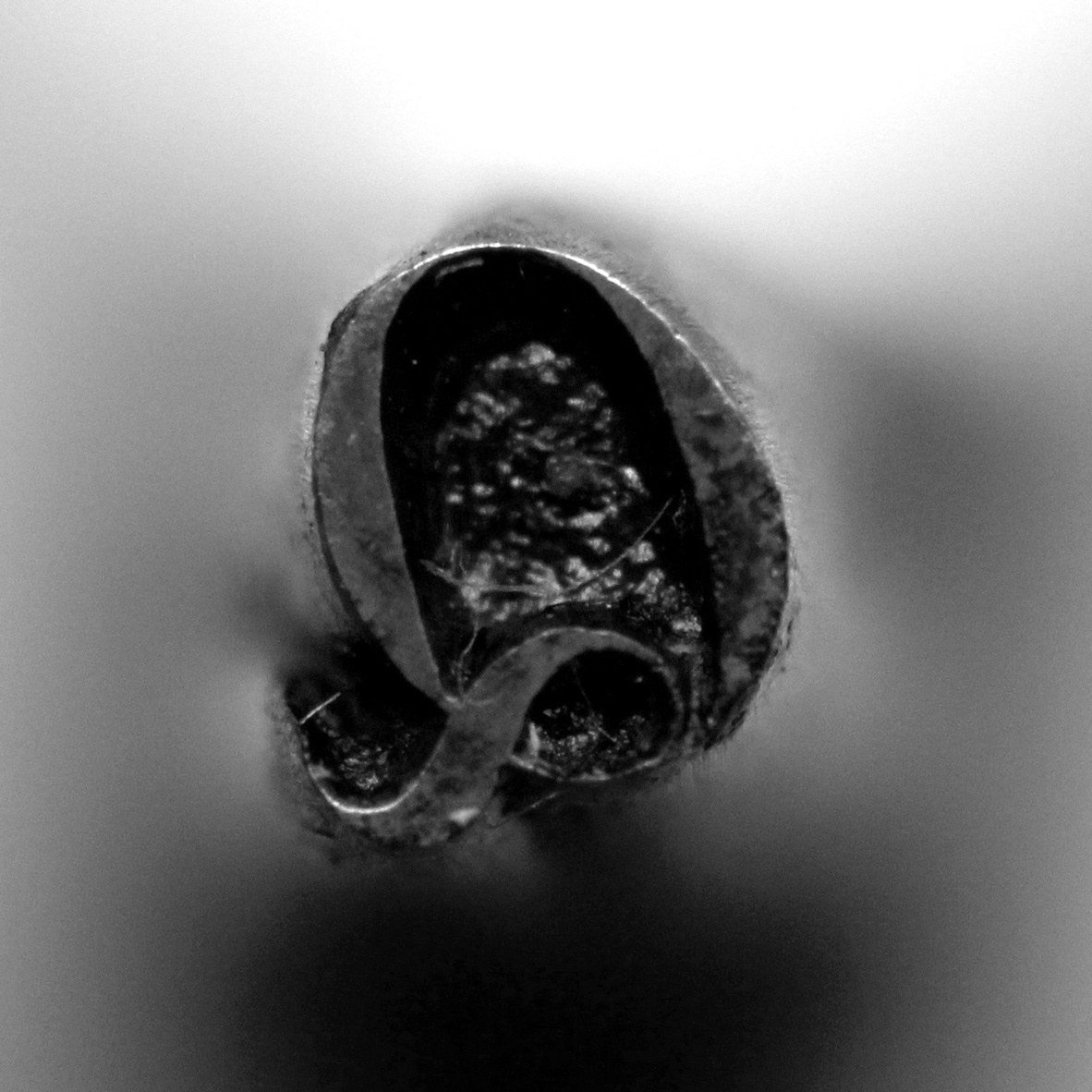

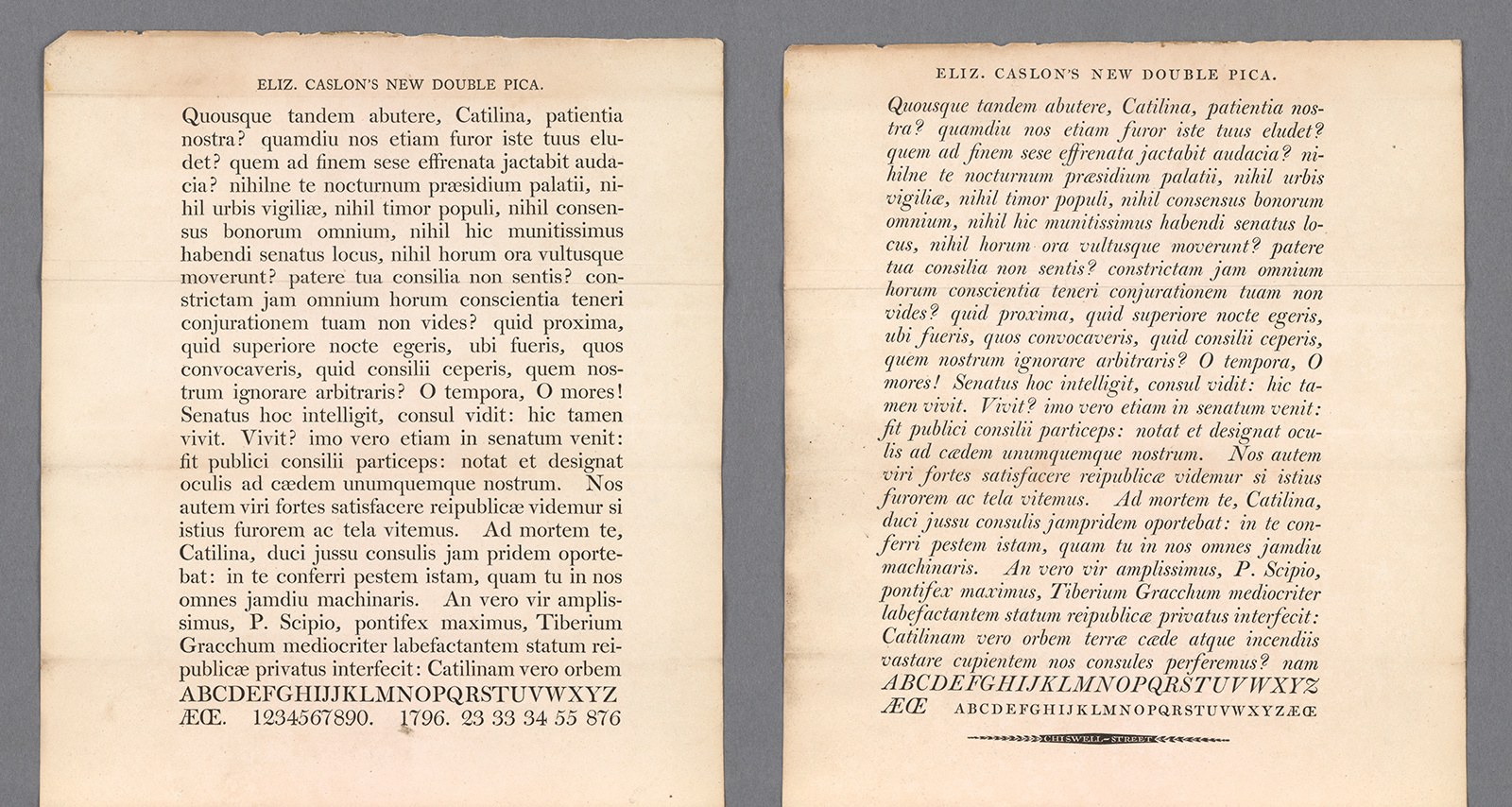

The model for Brunel Text, Caslon’s English No. 1 (14 pt), cut by John Isaac Drury at the turn of the eighteenth century for Elizabeth Caslon. As shown in Poetry of the Anti-Jacobin, 4th Edition, London, 1801. Printed by William Bulmer.

As Bodoni is Italian and Didot is French, Brunel is a British modern. Together, they share many commonalities of a style that swept away all that came before it in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: each displays a higher than normal contrast between thick and thin strokes, vertical stress, and a reduction and rationalization of form. In detail, however, they are distinct in showing how regional and nuanced the style can be. While the continental moderns achieved a fame that has outlasted their masters (how many Didot and Bodoni revivals are there?), a particular name or style of a British modern has never been as dominant.

Brunel encapsulates the qualities that identify the British variant of the modern style. It combines European influences with a set of more localized details and traditions that signify a starting point for the stylistic departure of the nineteenth century and the visual revolution that followed. As such, Brunel represents the starting point for the Commercial Classics series and embodies the ideas which the first designs explore. From the structure inherent in Brunel, we can see how these were developed into the fat faces, slabs, Italians, and sans forms that were the defining styles of the nineteenth century.

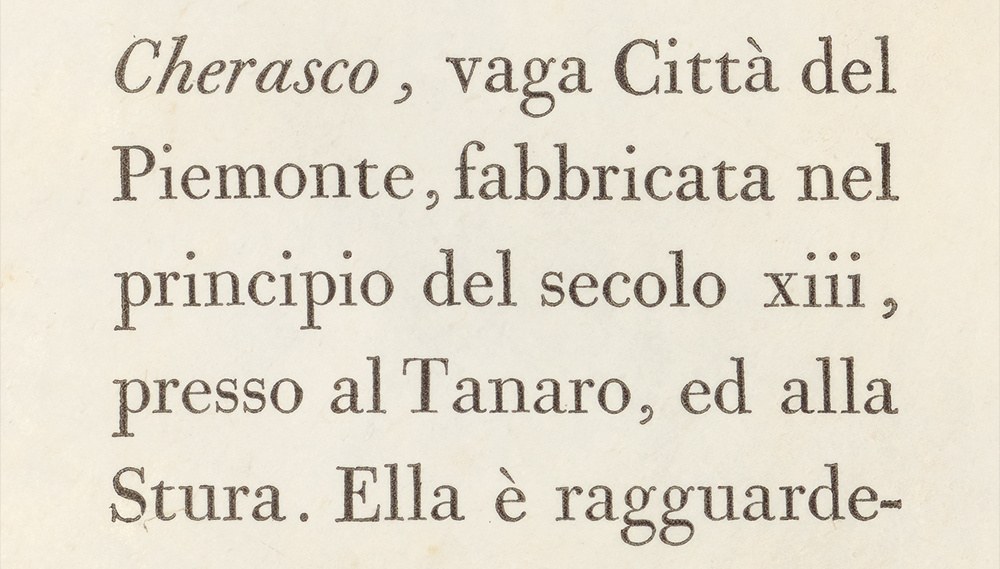

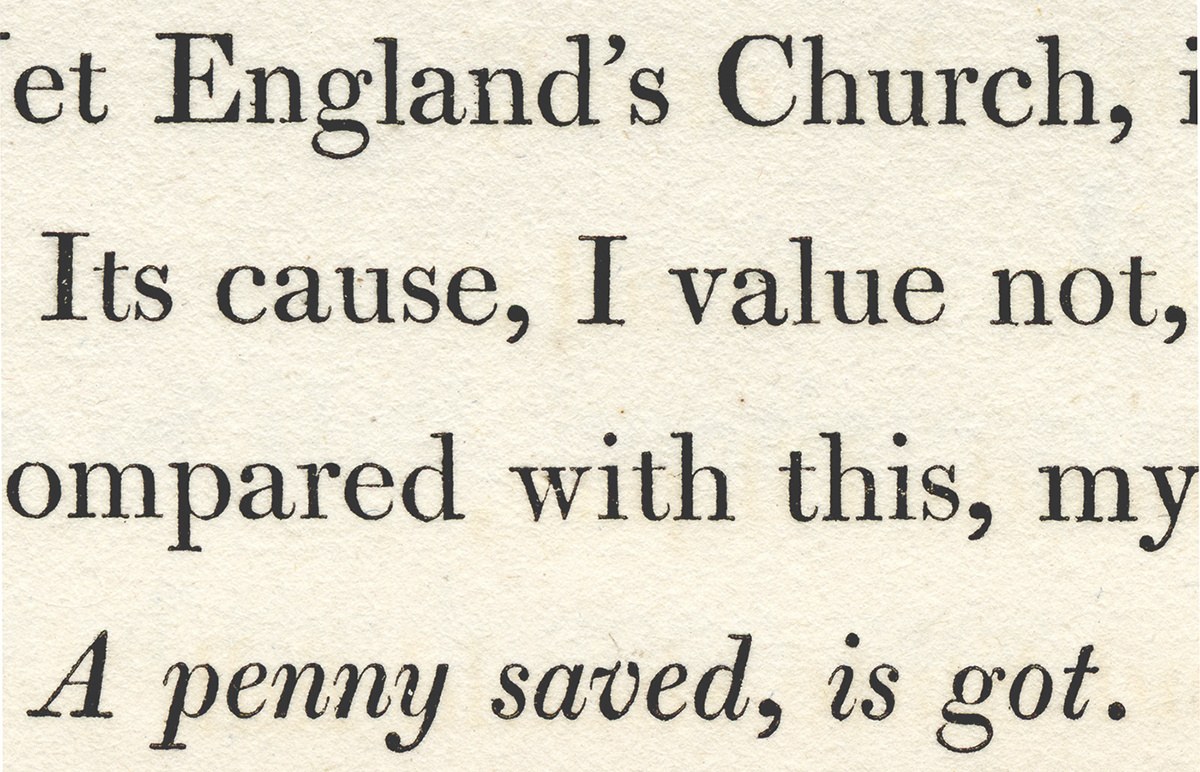

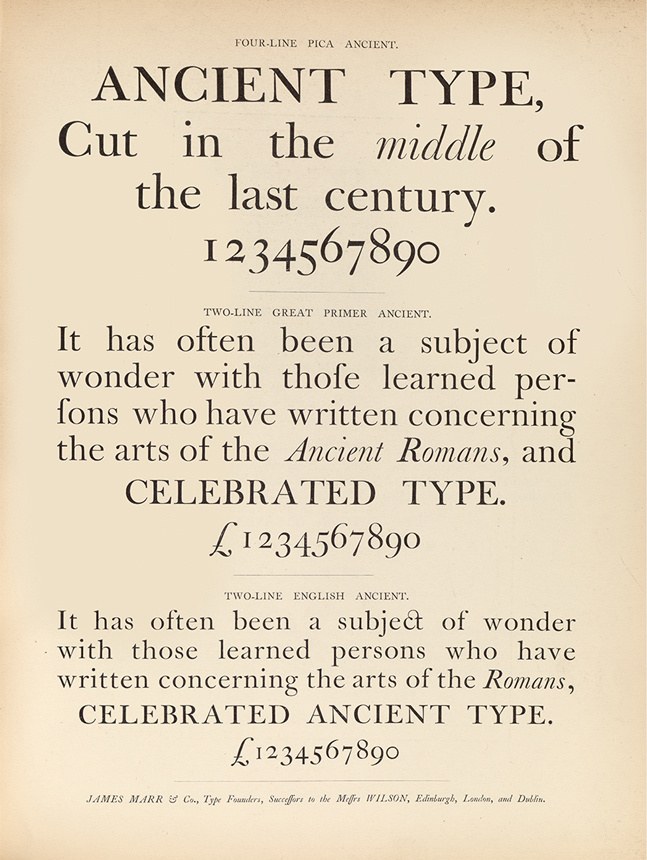

The famed transitionals of Alexander Wilson & Sons of Glasgow, cut in the second half of the eighteenth century, following the model John Baskerville pioneered. After the firm’s collapse in the 1840s, much of the stock was taken over by Marr, Gallie, & Co. In its later iteration as James Marr, they reissued the Wilson faces. Specimen of Modern and Ancient Printing Types, &c. by James Marr & Co. c. 1866. St Bride Library.

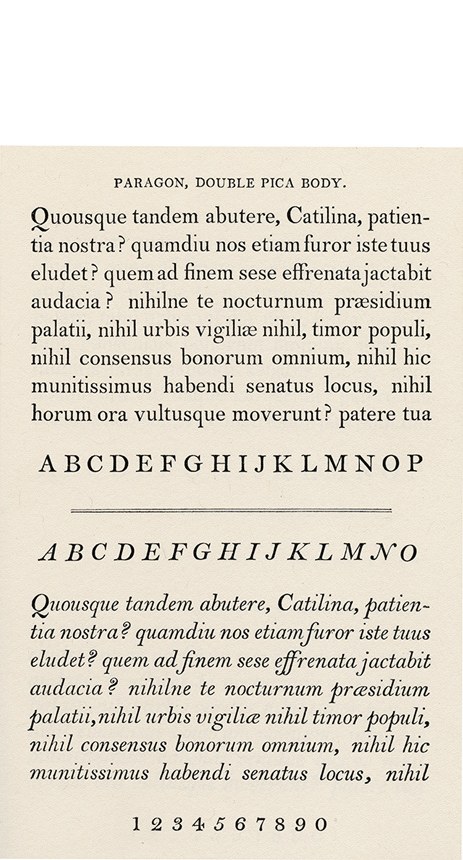

The first British modern as cut by Richard Austin, originally cut for John Bell. Austin’s modern has a gentler approach to letterforms than that of the Didot modern and remains localised in detail. A Specimen of Printing Types by S. & C. Stephenson, 1796 (facsimile edition, Printing Historical Society, 1990).

The first moderns for the Caslon foundry were cut by John Isaac Drury at the end of the eighteenth century for Elizabeth Caslon. The Double Pica was cut in 1796, of which the punches survive at St Bride Library. The smaller size Pica is dated 1799 and the English size (on which Brunel is based) was cut before 1801. This specimen is unique and from the New York Public Library.

Larger and Larger

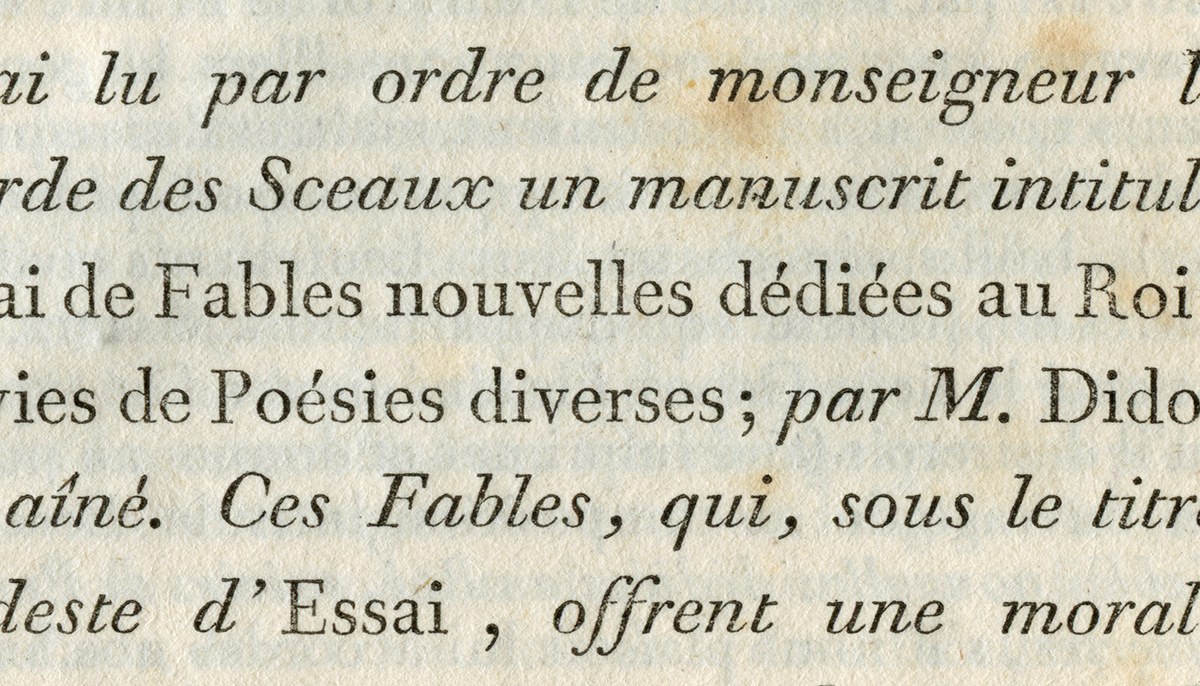

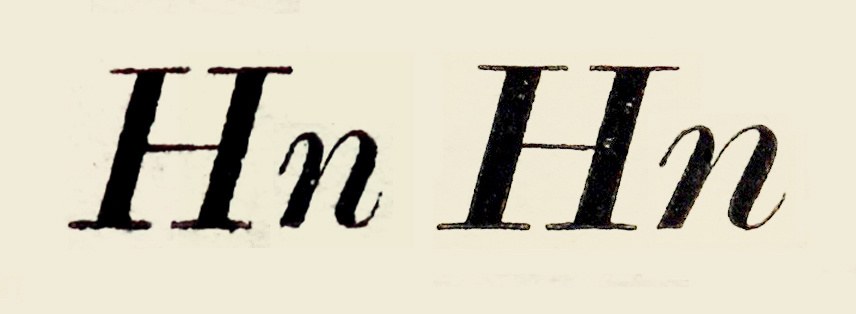

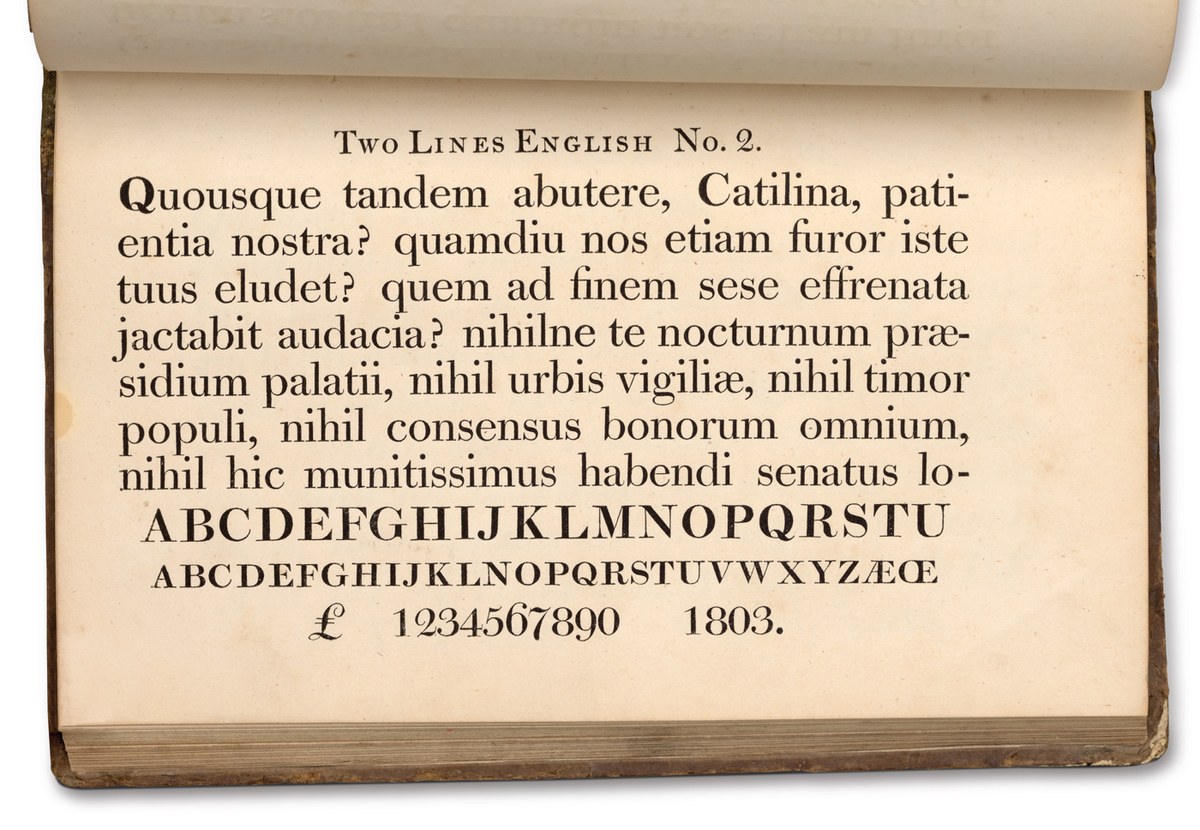

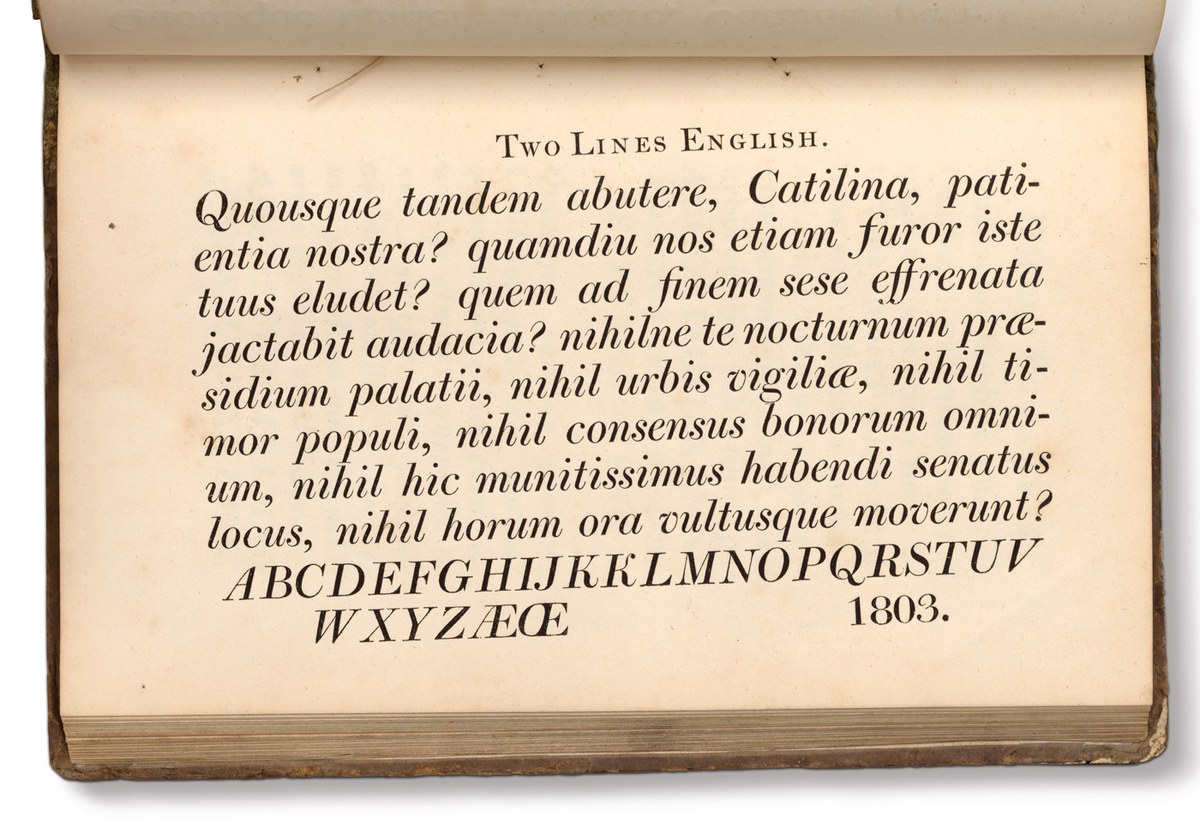

Two Lines English No. 2, cut in 1803. The punchcutter is unidentified, though it could be speculated they are the work of John Isaac Drury. Specimen of Printing Types by Caslon & Catherwood, undated, but before 1821. St Bride Library.

Italic of Two Lines English, cut in 1803. The italic is both wider and more angled than the text sizes; note the unusual K and swash form. Specimen of Printing Types by Caslon & Catherwood, undated, but before 1821. St Bride Library.

Bolder and Bolder

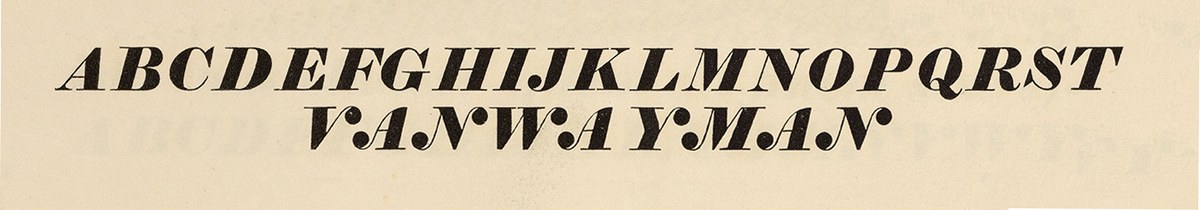

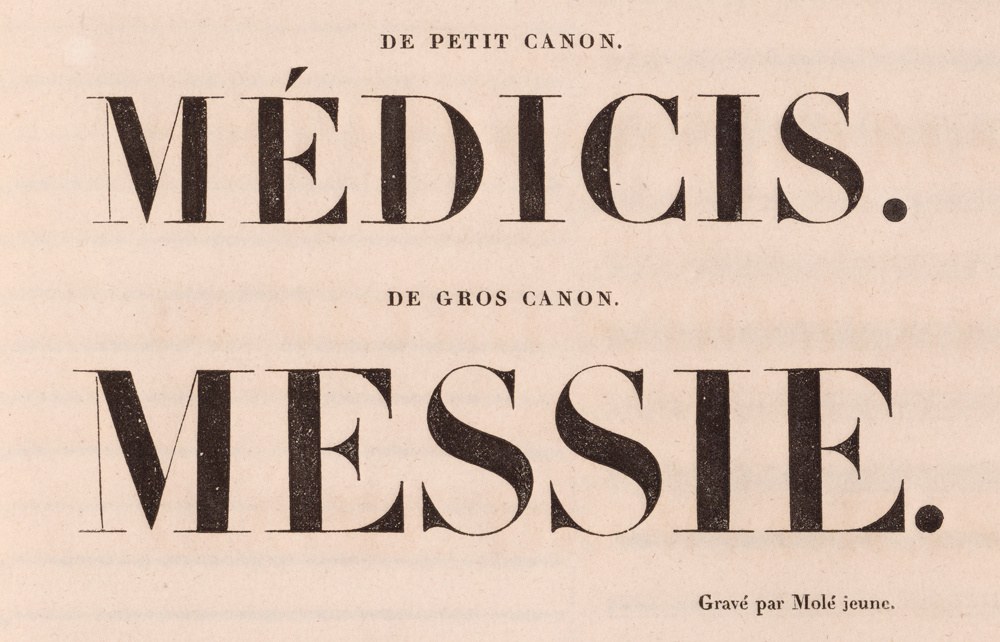

Large-sized bold modern type, produced by Fry and Steele during the first decade of the nineteenth century. This sample shows the direction that all foundries would follow in the next decade, culminating in the heaviest fat faces. Specimen is undated, but has various pages and watermarks dated between 1804–10. St Bride Library.

Brunel differs from the model in that all the weights were designed to join together, from the roman that Drury would have cut, through to a black that belongs to the following decade. Modern methods also allow the designer to create great modulation in the weight range quickly.

The modern marks the beginning of the nineteenth-century explosion in new letterforms. The first of the moderns created by Drury for the Caslon foundry were exemplary of the style, showing a maturity and confidence in execution that match those of the continental masters. In Brunel, Drury also becomes the starting point for Commercial Classics, with this revival encapsulating the aims of the new venture, taking the past as a starting point from which to recreate and expand, offering something new, and—most importantly—useful with what contemporary designers expect from modern families.