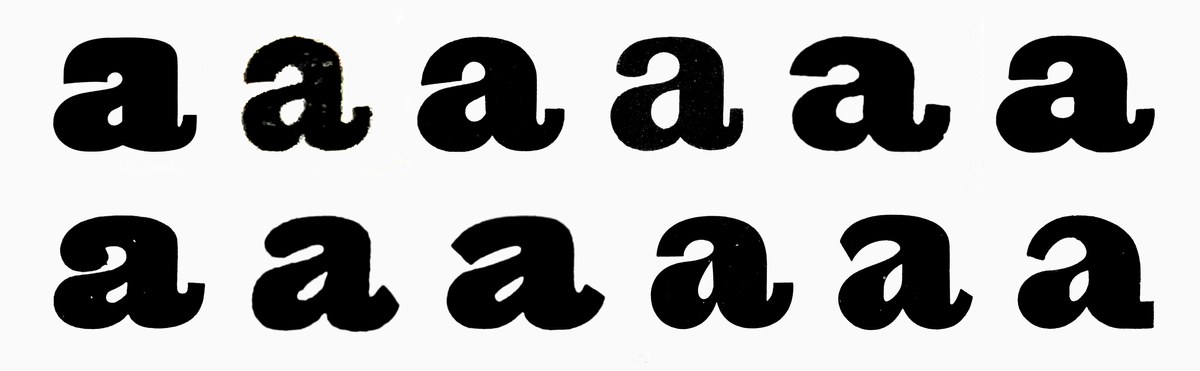

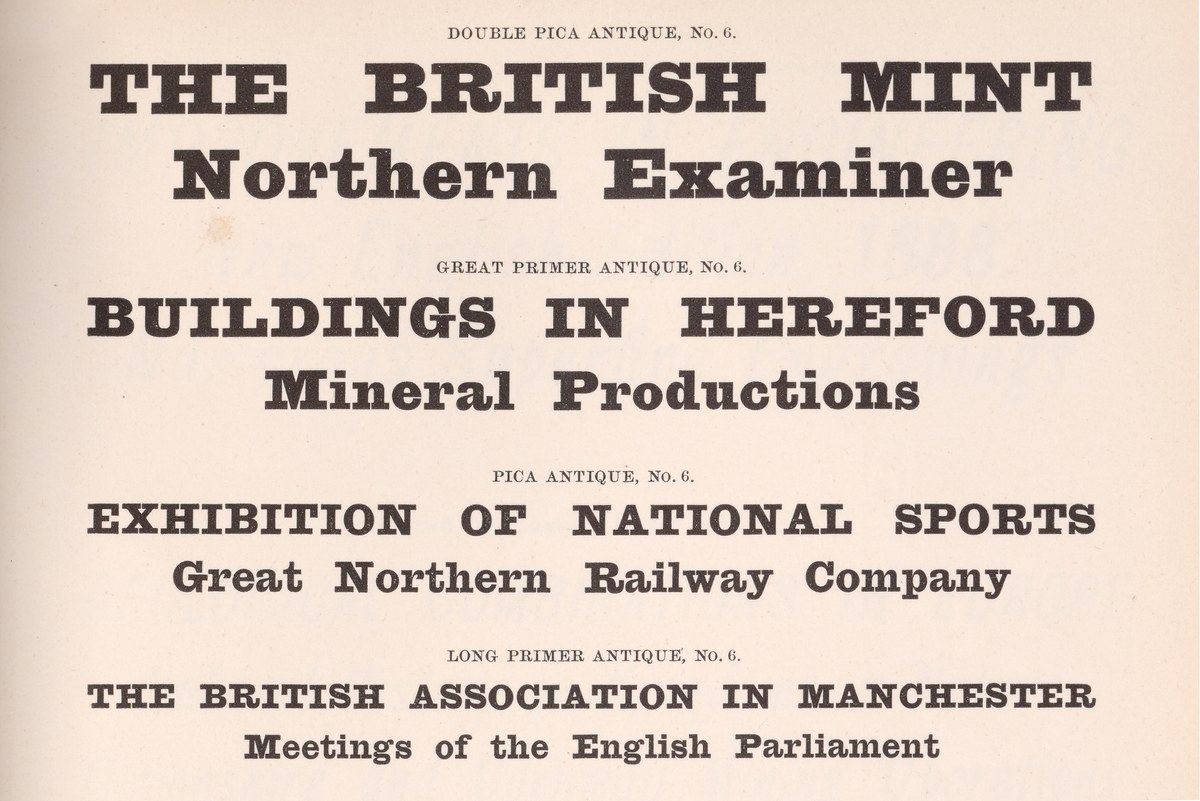

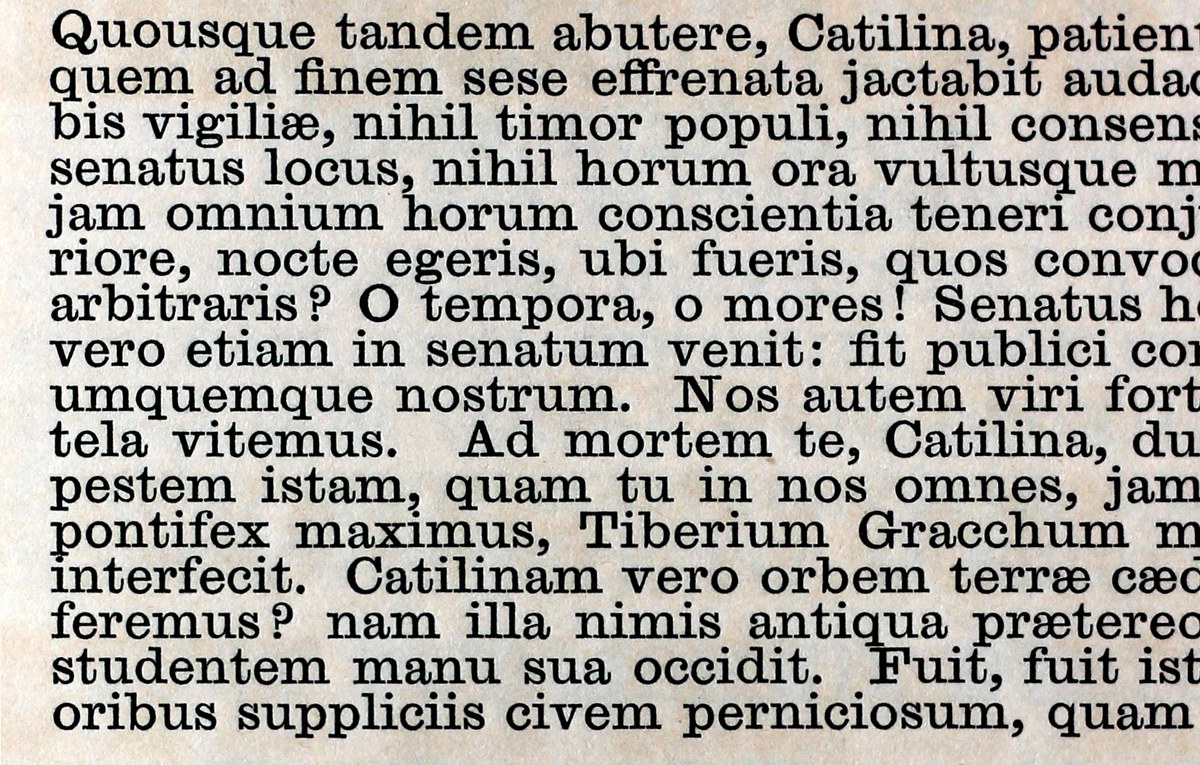

Antique No 6

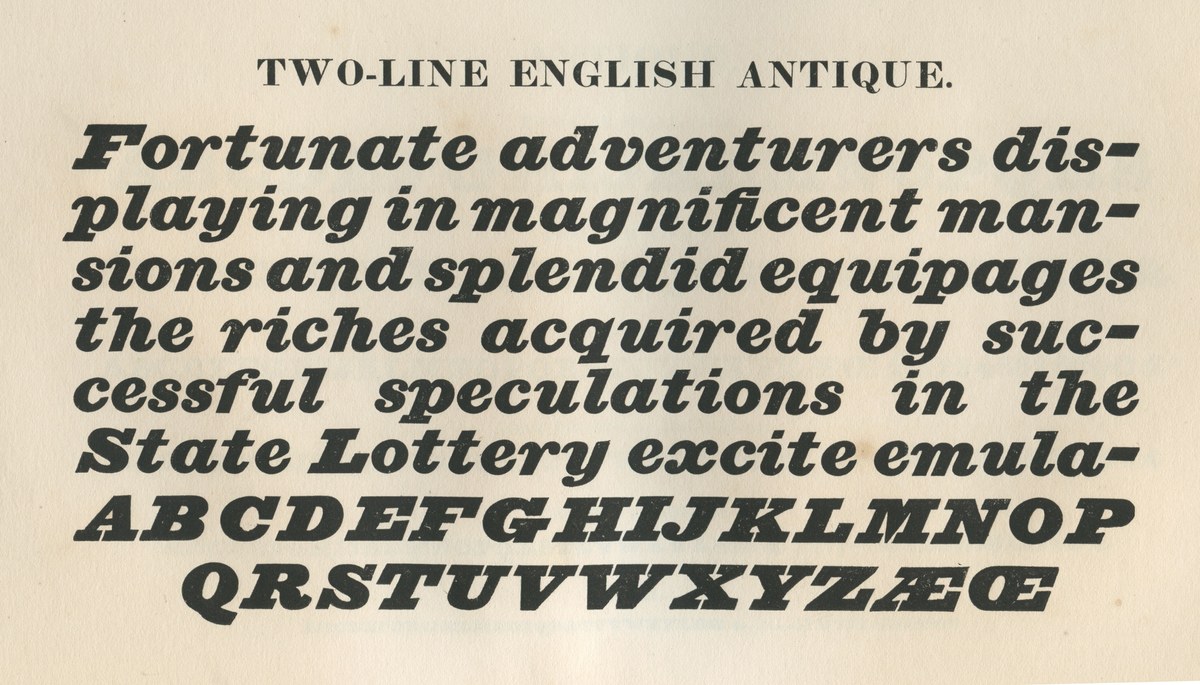

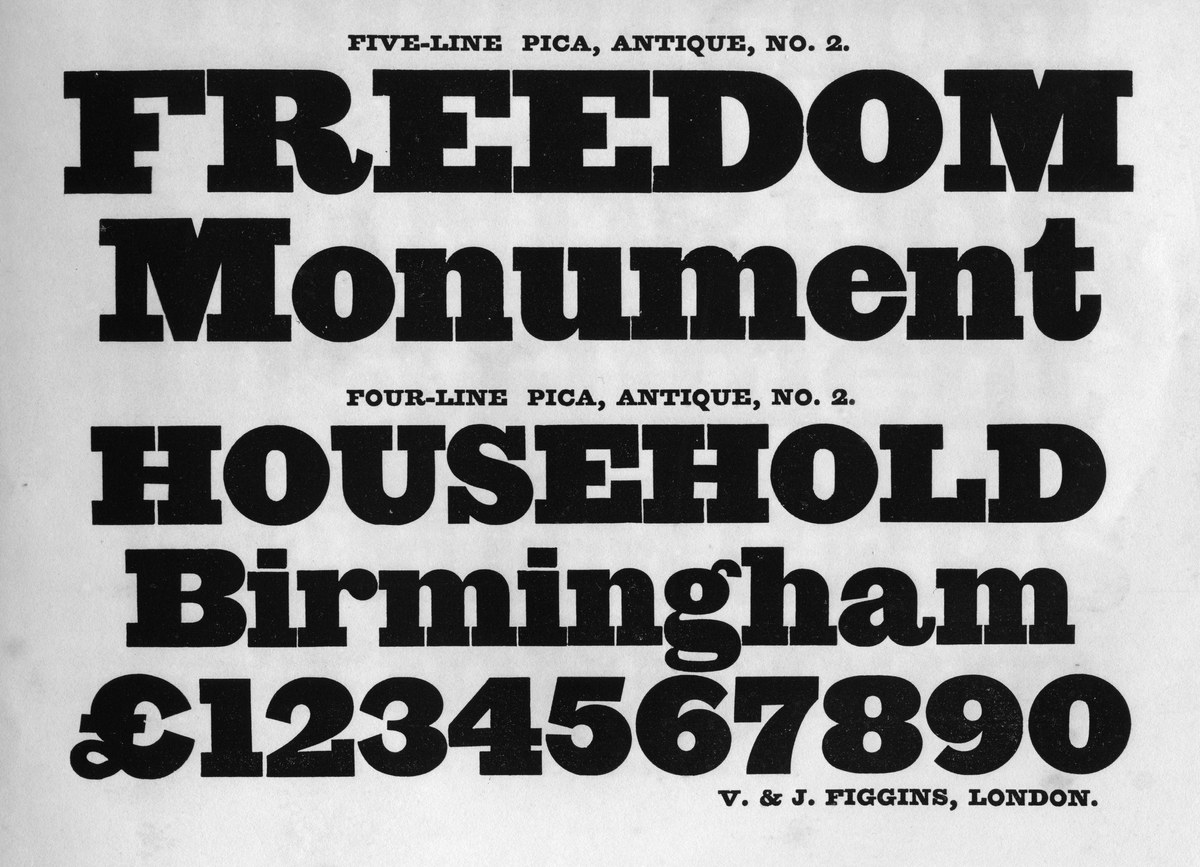

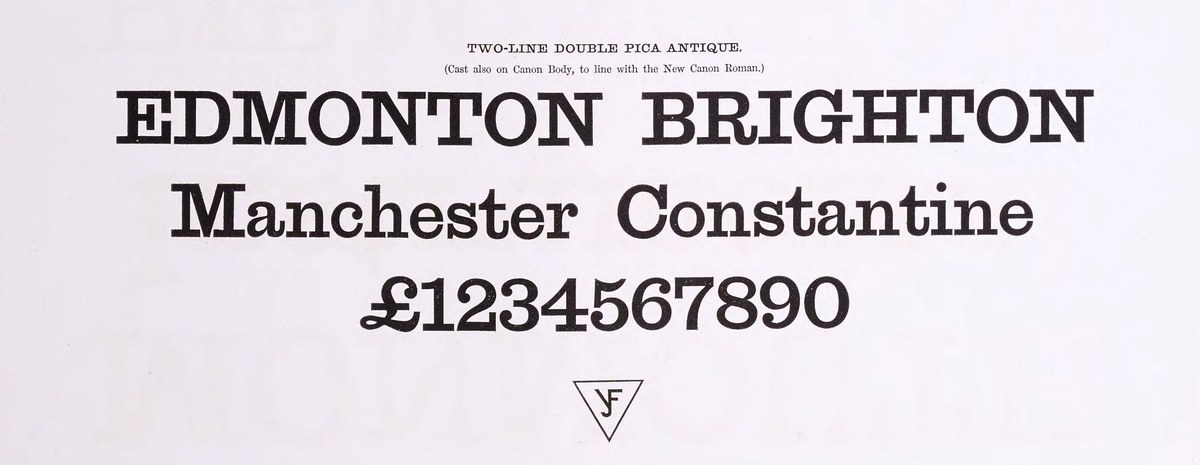

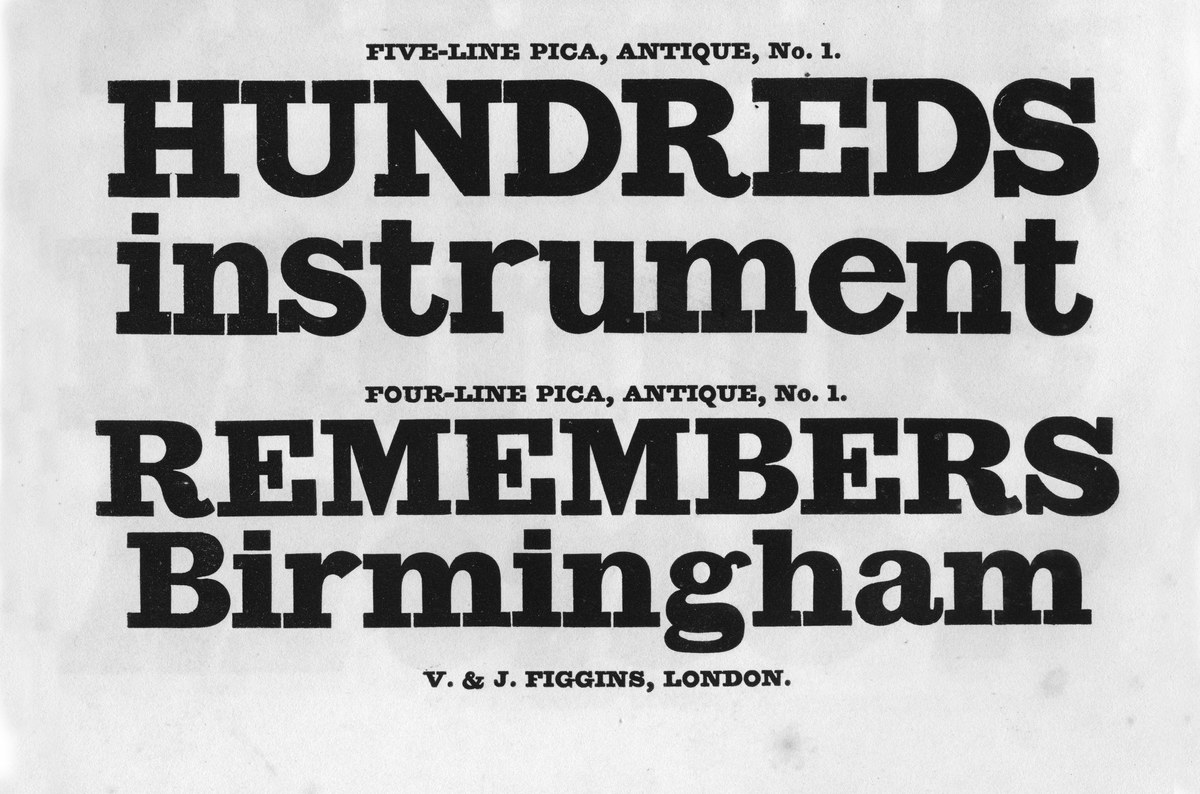

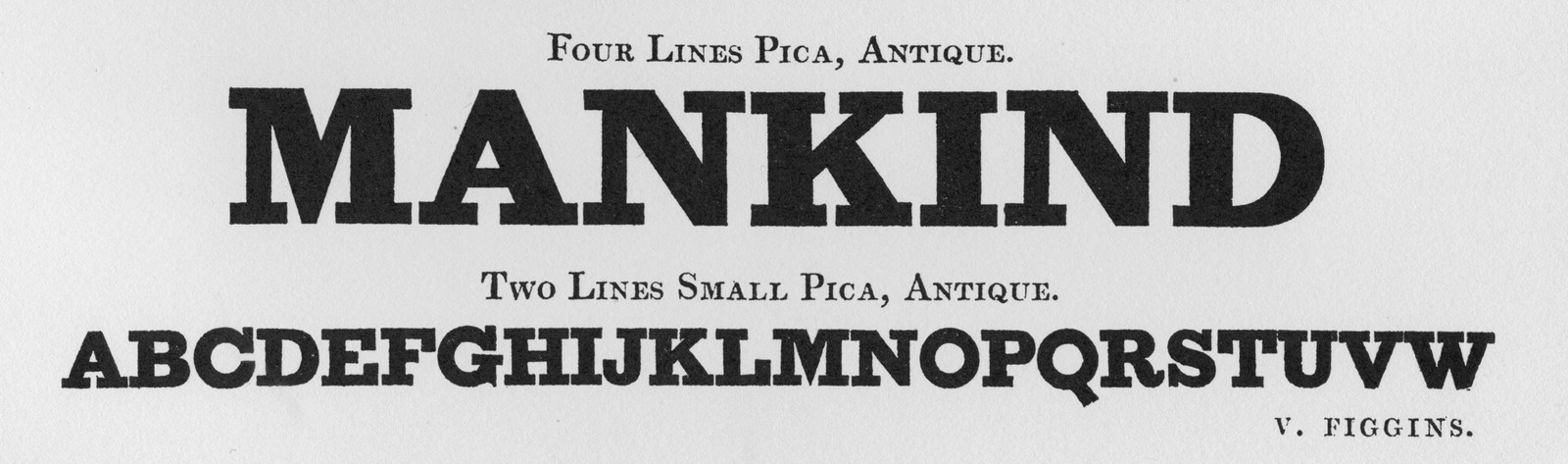

The first appearance of the slab serif: Four Lines and Two Lines Small Pica Antique. As shown in Vincent Figgins: Type Specimens, 1801 and 1815, Reproduced in facsimile, 1967.

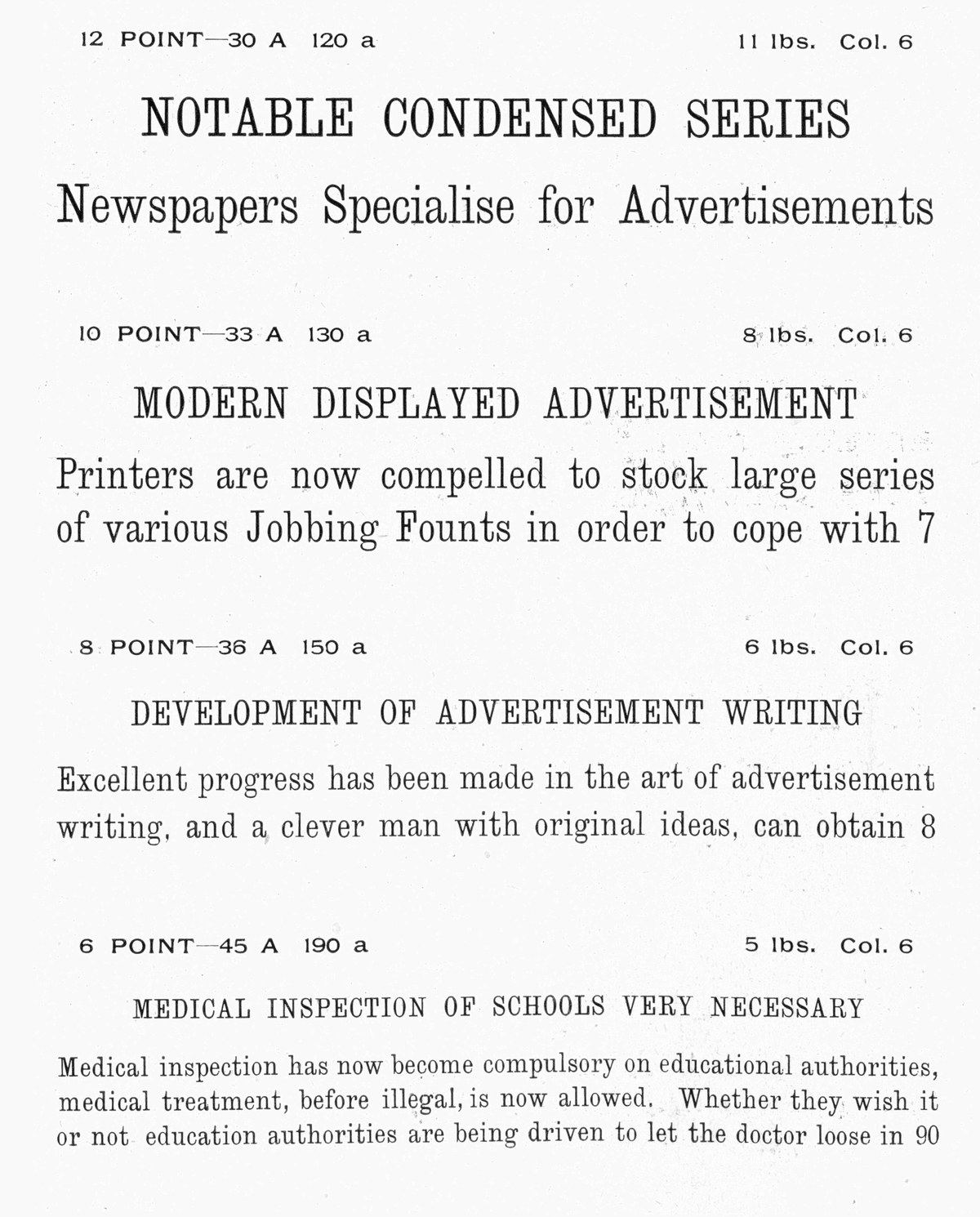

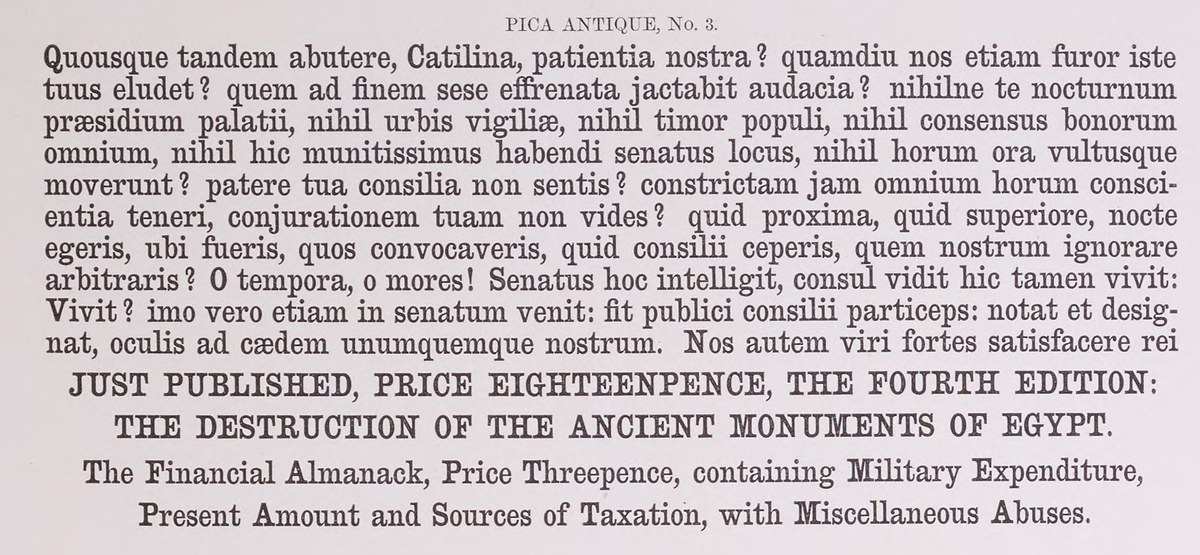

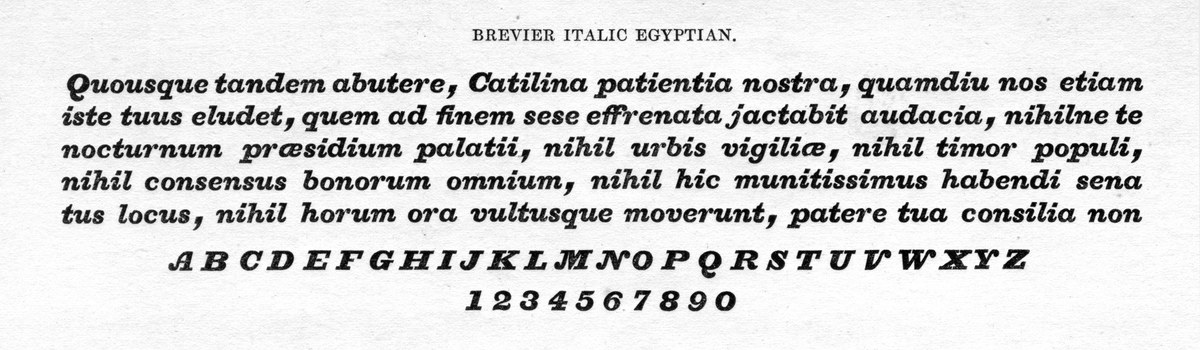

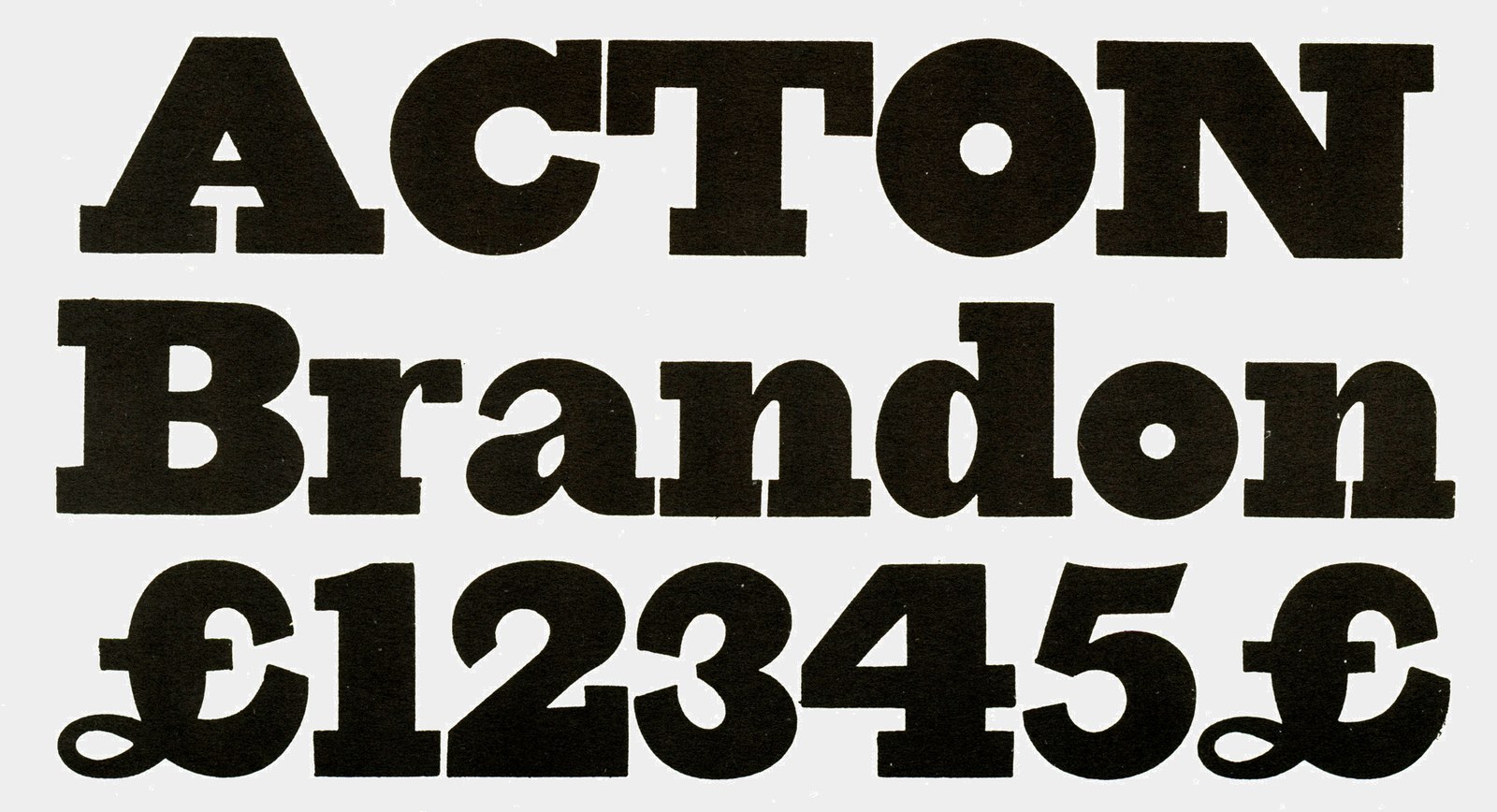

An early slab by Edmund Fry suggests how some foundries wrestled with the new style. Geometry is clearly used in the O, C, and o characters, their lack of weight variation distracting from the overall colour. As shown in Specimen of Modern Printing Types by Edmund Fry, 1828. Facsimile, Printing Historical Society, 1986.

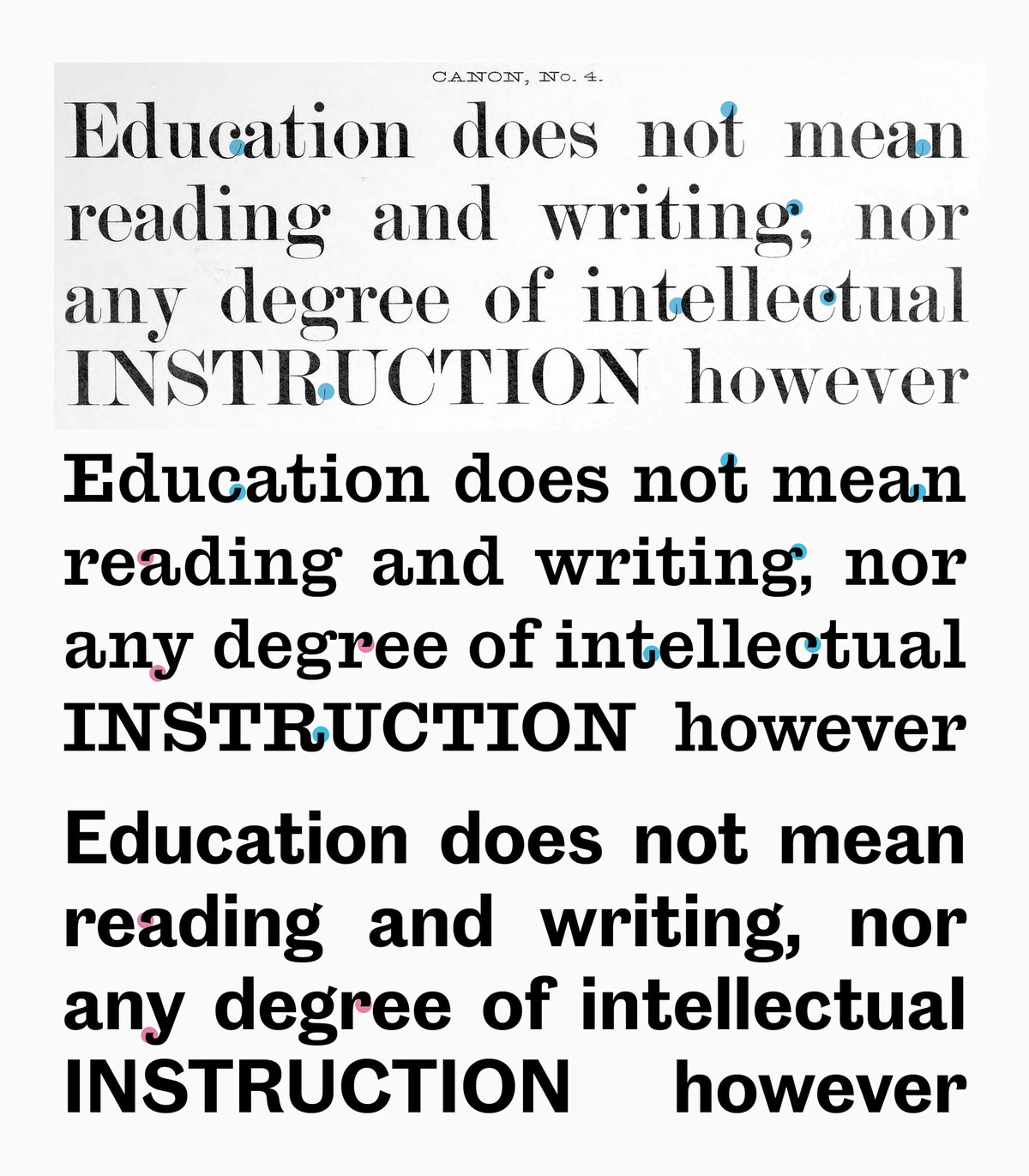

‘The most brilliant typographic invention of the century’

Antique No. 6

Antique No. 6 Reborn

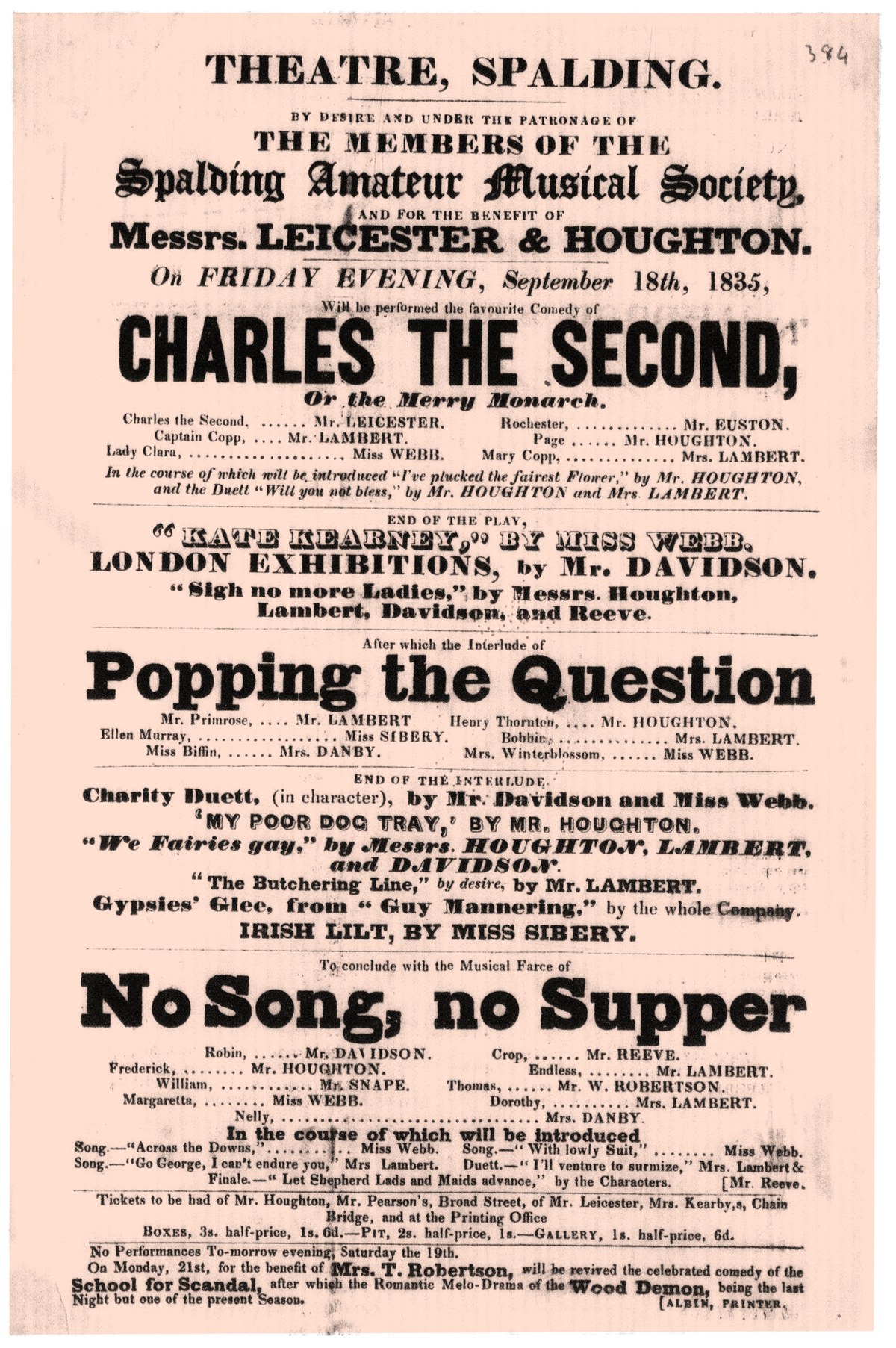

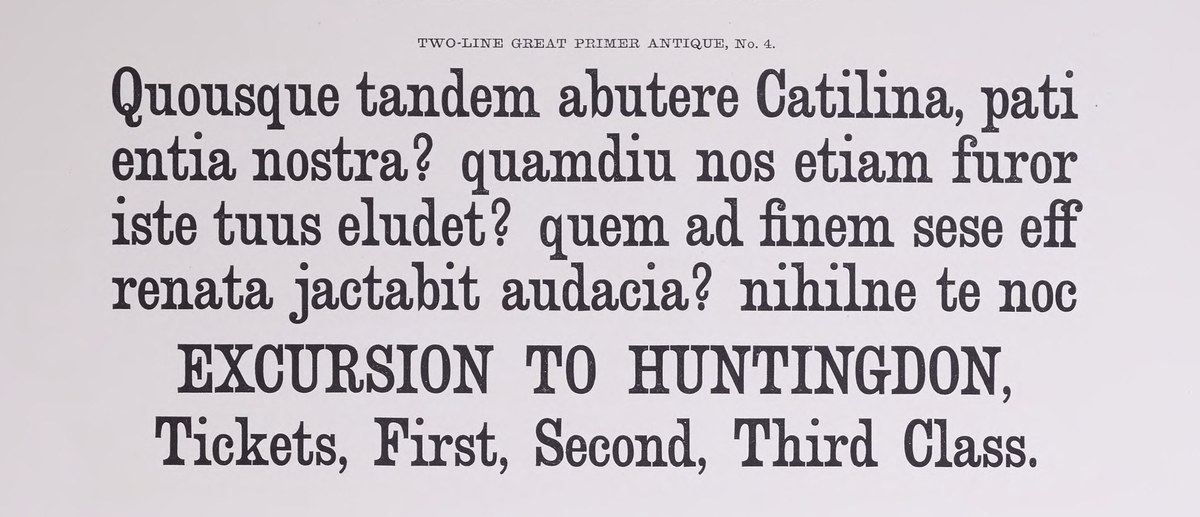

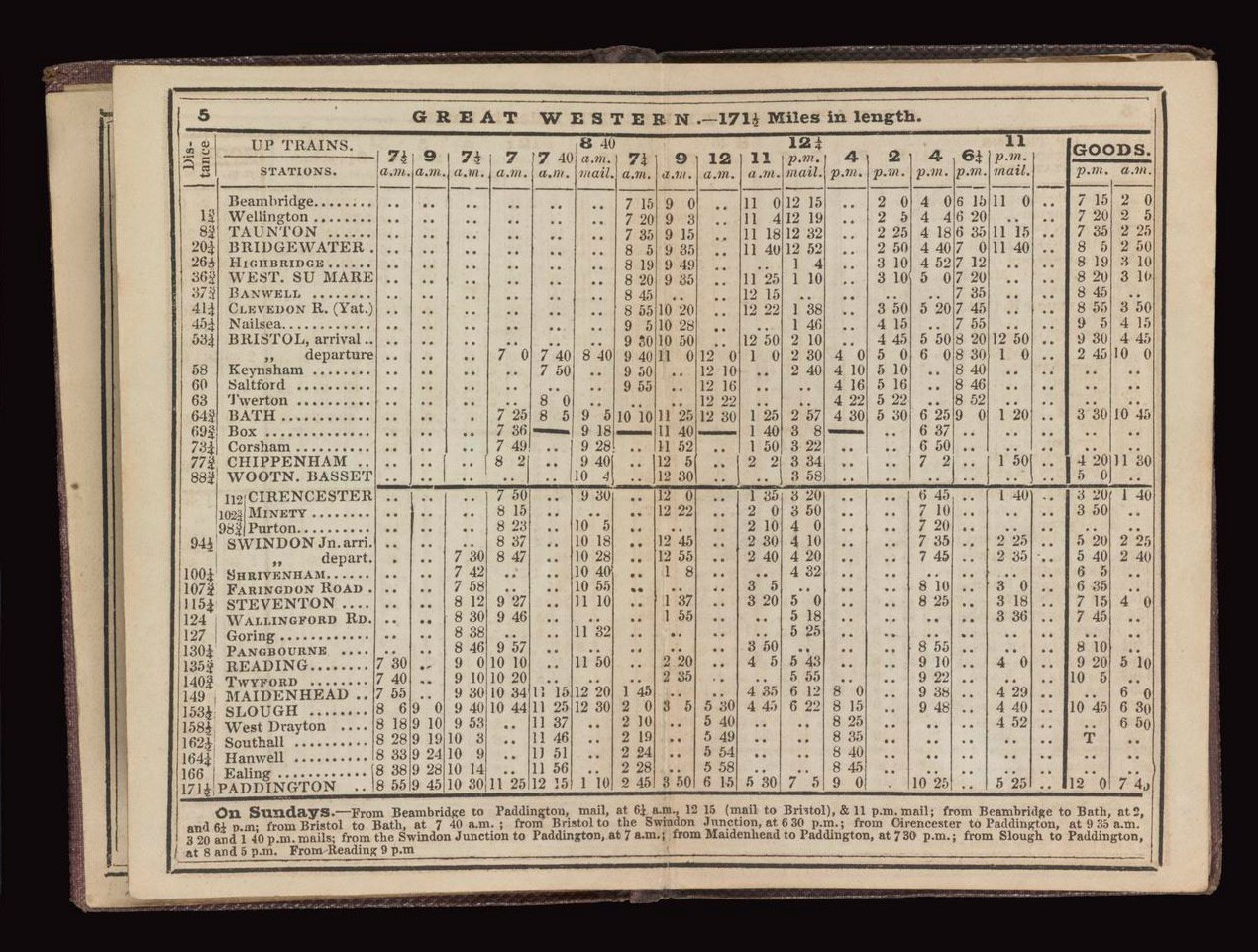

Slab serif used as a bold companion to a modern. Nineteenth-century printers mixed and matched styles where emphasis was needed, such as in this early example of a railway timetable. As shown in Bradshaw's Railway Companion timetable, 1843. Science Museum Group, reproduced under Creative Commons.

The specimen has a watermark for 1817, which suggests that the type itself may be dated to then.

Confusingly, Egyptian was the name Caslon IV had used for the first sans serif type, and can be seen in contemporary literature referencing the sans form.

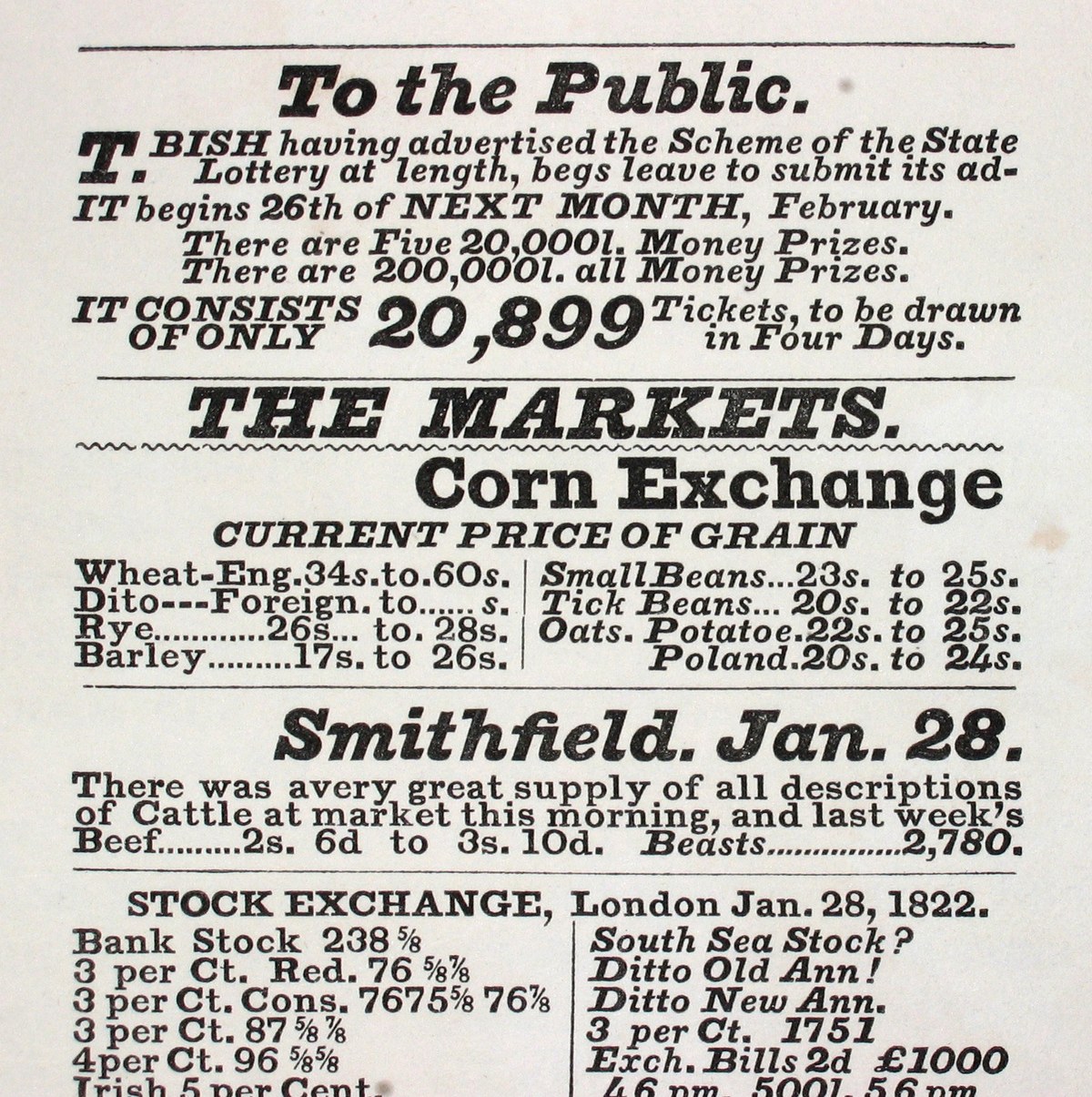

A lottery bill by Swift & Co., 1810 from the British Library as shown in James Mosley’s, The Nymph and the Grot, an update.

Second edition, 1976. See also “Slab-serif type design in England 1815–1845,” Journal of the Printing Historical Society, No. 15, 1980/81, which is the most comprehensive study of this period.

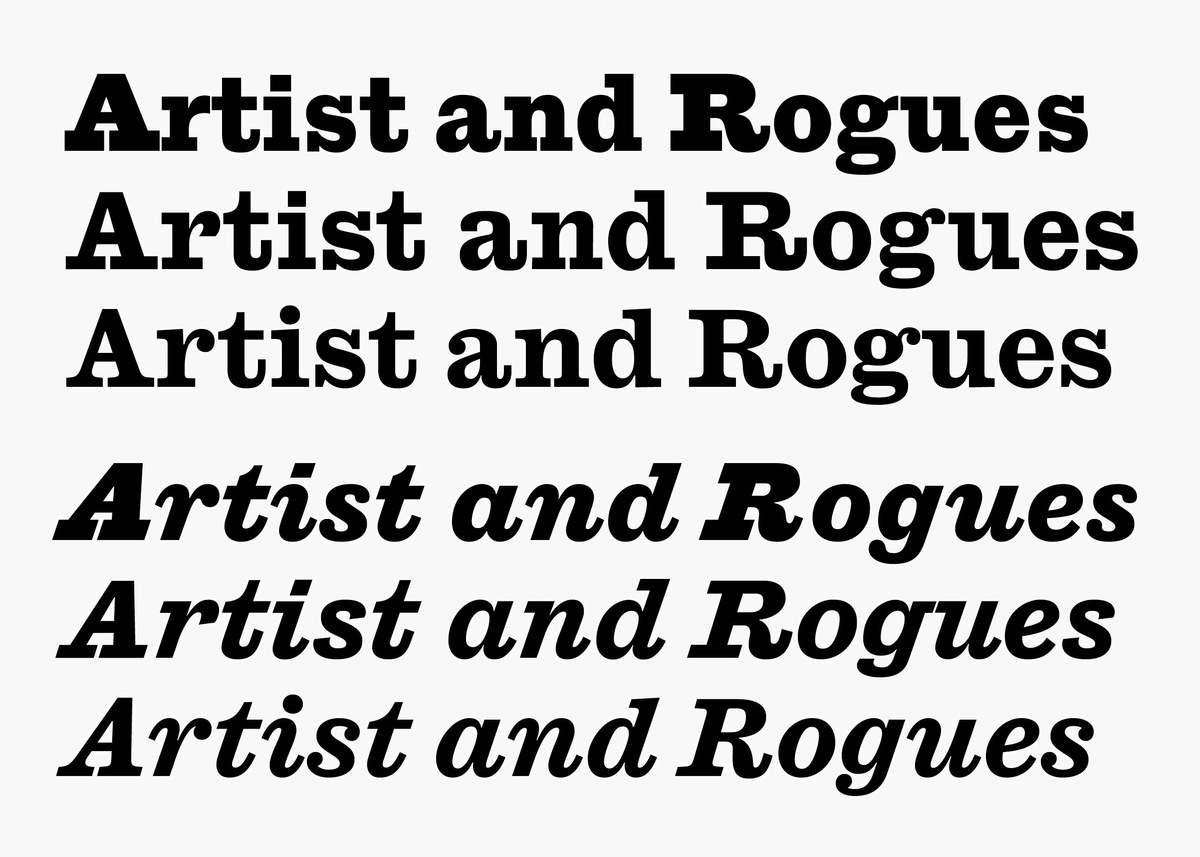

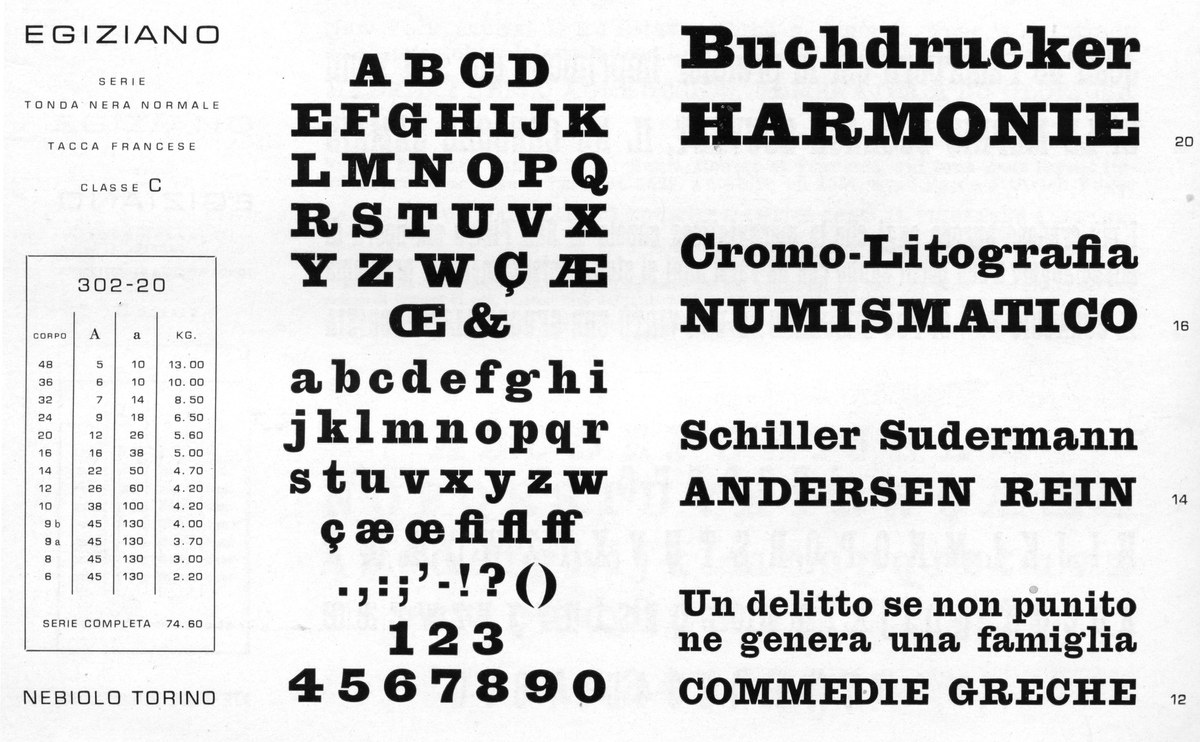

The design can also be seen in German founders’ specimens. For example, in Stempel, it’s called Bret Fette Egyptienne.

Hugh Hughes was a punchcutter, famed for his music type, who worked for both Thorowgood and Caslon before setting up his own foundry.